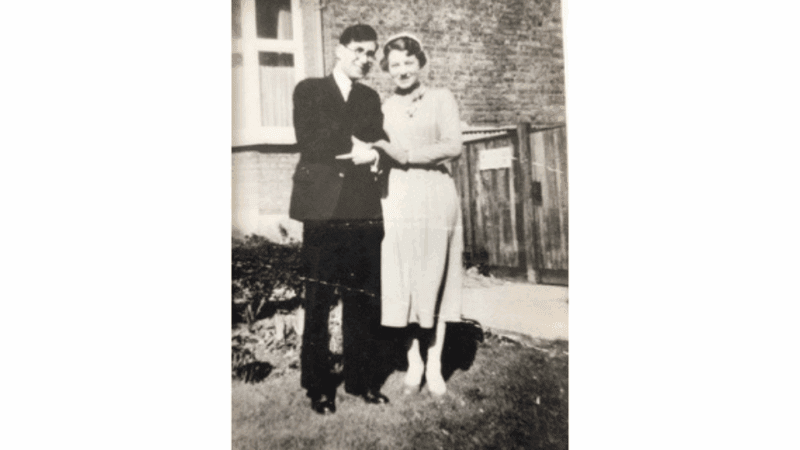

Sarah’s story – “Dementia UK was our saving grace”

Sarah reflects on reaching crisis point when her husband, David, was diagnosed with young onset dementia and the support her family have since received from Dementia UK.

There may come a time when a person with dementia is unable to make decisions, for example about their care and finances. A lasting power of attorney appoints someone else to make decisions on their behalf, in their best interests.

On this page, our dementia specialist Admiral Nurses explain what a lasting power of attorney is, how to set one up, and who can take on the responsibility.

A lasting power of attorney (LPA) is a legal document that appoints one or more trusted individuals to be a person’s ‘attorney’ – someone responsible for making decisions on their behalf.

There are two different types of LPA in England and Wales. A person can decide whether to make one or both, and to name the same or different people as their attorneys for each.

This type of LPA gives the attorney the power to make decisions about the person’s health and welfare. This can include:

This type of LPA can only be used if the person with dementia lacks capacity to make their own decisions. However, medical professionals have overall authority on any clinical decision according to the person’s best interests.

This type of LPA is used to give an attorney the power to make decisions about property and money matters. This can include:

With the person’s permission, their attorney can make decisions under this type of LPA as soon as it is registered. However, the attorney must always act in the person’s best interests, keep clear records, and keep their own finances separate from the person they are attorney for.

LPAs are valid in England and Wales. In Scotland, the equivalents are called ‘welfare power of attorney’ and ‘financial power of attorney’. In Northern Ireland, there is only one type, called ‘enduring power of attorney’. This covers financial decisions only.

Most people with dementia will reach a point where they can no longer make informed decisions. This is referred to as ‘loss of mental capacity’.

Making an LPA before the person with dementia loses mental capacity means they can state who they would like to make decisions on their behalf. The attorney is then legally bound to make decisions in the person’s best interests, considering their wishes, if they lose mental capacity.

Even if someone is married or in a civil partnership, it is important to make an LPA, as their partner is not automatically entitled to make decisions on their behalf.

Mental capacity is a legal term that refers to a person’s ability to make informed decisions. A person is judged to have lost mental capacity if they cannot:

Typically, a health or social care professional will assess whether a person has capacity using the principles outlined in the Mental Capacity Act. You can read more about how it is assessed in our information on mental capacity and decision-making.

A health and welfare attorney can only make decisions using their LPA if the person has lost capacity. However, a property and financial affairs attorney can make decisions on their behalf as soon as the LPA is registered, with the person’s agreement, even if they still have mental capacity.

Mental capacity may fluctuate. For example, a person with dementia may temporarily lose capacity if they are experiencing delirium (sudden, extreme confusion, often due to an infection), but it might return once the issue is addressed. Or a person who experiences sundowning (a state of intense confusion and/or anxiety that typically occurs in the evening) may have the capacity to make a particular decision in the morning, but not in the evening.

Capacity is also ‘decision-specific’. For example, a person may have capacity to decide on something simple, like what they want for dinner, but may not be able to make a complex decision such as whether to sell a business.

When someone is diagnosed with dementia, it’s important to draw up an LPA as soon as possible. While this may not seem urgent, a person can only make an LPA while they have mental capacity. It is impossible to know how quickly a person with dementia will deteriorate, so making an LPA should be a priority.

If a person loses capacity and doesn’t have an LPA, it will be more difficult for someone else to make decisions on their behalf. They may have to apply to the Court of Protection to be appointed as the person’s ‘deputy’. This can be a complex and expensive process, so setting up an LPA in advance is strongly recommended.

It’s sometimes thought that a person with a diagnosis of dementia can’t make an LPA, but this is not true. As long as they still have mental capacity, which many people with dementia will retain for some time, they can make an LPA.

To make an LPA, the person must be over the age of 18 and have the mental capacity to make their own decisions. They do not need to live in the UK or be a British citizen.

Simon lives in New Zealand and cares for his dad, who has Alzheimer’s disease and lives alone in the UK.

Read Simon's story“Putting everything in place has been a full-time job and very challenging in dealing with lots of different people and organisations. I have lasting power of attorney for my dad, which means I can make decisions on his behalf.”

You can make an LPA yourself or with a solicitor.

Attorneys must be over the age of 18, capable of managing their own finances, and trusted by the person making the LPA. For example, it could be their partner, another family member, such as an adult child, a friend or a professional, such as a solicitor. It is a good idea to think about:

It is possible to nominate multiple attorneys. In this case, the person must specify which decisions the attorneys must make together (‘jointly’), and which can be made by one attorney alone (‘severally’). For example, the person may state that big decisions like selling a house need to be made jointly, but smaller decisions, such as withdrawing money to pay for their food shopping, could be made severally.

If you are making an LPA with a solicitor, they will provide the necessary forms. To get the LPA form yourself, you can:

The applicant can fill in the LPA form themselves, with the help of another person – for example a family member, friend or solicitor – if they need it. They must, however, be able to sign it themselves.

The LPA forms must be signed by:

Find out more about how to fill in an LPA.

The person applying for the LPA can nominate up to five people to be notified about the application and given the chance to raise any concerns. This is optional, but it helps ensure the person is not being pressured into making the LPA.

To do this, you must fill out a Form to Notify (LP3).

In England and Wales, the cost of registering each LPA is £82. If the person makes both a health and welfare LPA and a property and financial affairs LPA, the total will be £164.

It’s worth checking if the person qualifies for a fee reduction or exemption due to their circumstances.

These figures are correct as of September 2025, but please check the latest fees.

In England, once the LPA forms are complete, they should be sent to the Office of the Public Guardian at the address on the forms, enclosing the fee.

It usually takes eight to 10 weeks for registration to be completed, provided there are no errors on the form. Once registration is complete, the Office of the Public Guardian will send a registration notice confirming that the LPA is active.

To register a power of attorney in Scotland, the form can be submitted online or by post. In Northern Ireland, the enduring power of attorney form should be completed and signed in advance but is only registered with the court once the person has lost capacity.

There may be situations where an LPA needs to be changed or ended.

The person with the LPA (if they still have mental capacity) or their attorney must tell the Office of the Public Guardian (OPG) if:

A person can remove an attorney from their LPA for any reason, as long as they have mental capacity. They should do this by sending a ‘partial deed of revocation’ to the Office of the Public Guardian, using this specific wording.

If the person wishes to appoint a new attorney, they will need to end their LPA and make a new one. However, when the person makes their LPA, they can nominate someone to replace their attorney if the person/people they originally named can no longer act on their behalf.

A person can end their LPA if they have the mental capacity to make that decision. They will need to write to the Office of the Public Guardian, enclosing:

An LPA will end automatically in certain circumstances, for example if the attorney loses mental capacity or dies.

For further information on how to change or end an LPA or remove an attorney, visit the Gov UK website.

To ensure that the LPA is registered as quickly as possible and avoid paying additional fees, it is crucial to make sure there are no errors. Common mistakes include:

Read through all instructions carefully, and if you’re unsure, contact the Office of the Public Guardian. Read more about common LPA mistakes and how to avoid them.

It is important for attorneys to understand what the position involves and what the legal expectations and limitations are. Read about attorneys’ responsibilities.

The person with dementia must have the mental capacity to understand and sign the LPA documents. It’s not possible to make an LPA on behalf of someone who lacks mental capacity.

There are other ways to make decisions on a person’s behalf if they don’t have an LPA, such as applying to the Court of Protection to be their ‘deputy’, but these processes can be slow and expensive.

There are certain legal limitations to LPAs. For example:

The attorney must not:

Any decision made by an attorney could be checked by the Office of the Public Guardian or the Court of Protection, for example if there is reason to believe they have been misusing the person’s money.

To speak to a specialist Admiral Nurse about making an LPA or any other aspect of dementia, please call our free Dementia Helpline at 0800 888 6678 (Monday-Friday 9am-9pm, Saturday and Sunday 9am-5pm, every day except 25th December) or email helpline@dementiauk.org. Alternatively, you can pre-book a phone or video appointment with an Admiral Nurse.

A person with dementia can make and sign an LPA as long as they have the mental capacity to understand what they are doing. If they don’t have mental capacity, they can’t make an LPA.

A deputyship order enables someone to make a decision on behalf of a person who lacks capacity and doesn’t have an LPA. This will need to be authorised by the Court of Protection.

Yes, there can be more than one attorney. This is common if someone has multiple adult children, for example, and wants them all to have a say in making decisions. The person will need to specify which decisions must be made jointly, and which can be undertaken by a single attorney.

A person can have the same attorneys for both health and welfare and property and financial affairs, or different ones for each.

As long as someone has the mental capacity to do so, they can change their mind about their LPA. To find out about the steps to take, visit the Gov UK website.

A person can refuse to be an attorney if they don’t want to be named.

A person with dementia who lacks mental capacity can’t refuse a decision made on their behalf, in their best interests, by their attorney. However, if they have capacity, they can change or end their LPA. They will need to contact the Office of the Public Guardian.

Certain people can overrule decisions made under an LPA. For example, a doctor can overrule an attorney’s decision that the person with dementia should receive life-sustaining medical treatment if the person made an advance decision stating that they would not want to receive such treatment.

Sarah reflects on reaching crisis point when her husband, David, was diagnosed with young onset dementia and the support her family have since received from Dementia UK.

Jo reflects on the support she has received from her Admiral Nurse, Liz, since her husband was diagnosed with dementia.

Kerry reflects on her mum's dementia journey and her experience doing two of Dementia UK’s virtual event challenges.