Nat’s story – “Being a young carer can be lonely”

Nat reflects on her experience of being a young carer and the support she received from the Nationwide dementia clinic.

Going into hospital can be difficult for people with dementia due to the unfamiliar surroundings, people and routines. However, good preparation and support can help make their hospital admission easier.

If a person with dementia is going into hospital for a planned procedure, they should be sent written information in advance, including details about the expected length of their hospital stay and whether they can eat or drink beforehand. They may also have a pre-operative assessment (‘pre-op’), which might involve tests like a blood pressure check and being weighed. This is an opportunity to ask any questions about their admission.

Before the person is admitted, let the relevant department know that they have dementia and of any needs related to their condition. It is also useful to complete a care passport/hospital passport which provides information to help guide their care, for example:

The hospital may have a care passport template, or you could use our life story template.

To help the person with dementia prepare for being in hospital:

On arrival, check that the hospital staff know that the person has dementia and give them a copy of their care passport and any other plans they have made to inform their medical care, such as an advance care plan, ReSPECT form or advance decision to refuse treatment – see ‘Making decisions’, below.

You may want to ask if you can stay with the person while they settle into the ward, and if there is a dementia specialist Admiral Nurse or dementia team that could support them during their stay.

Being admitted to hospital in an emergency may be particularly unsettling for a person with dementia, so try to explain clearly why they need to go to hospital and what to expect when they get there.

It may be useful to keep a list of things to pack in their hospital bag in case of this situation, or even keep a bag prepared at home.

Make sure everyone involved in treating the person – including paramedics, if they require an ambulance – knows that they have dementia, and share any useful information such as advice on communicating with them.

If sitting in a waiting room is likely to cause the person distress, you could ask reception staff if there is another, quieter place they could wait. Try to provide distractions – for example, you could use your phone to look at photos together, or play music or a television programme (with headphones).

It may be helpful for another family member or friend to accompany you to the hospital so they can stay with the person if you need to have discussions with the medical staff.

Visits from family and friends can be a huge comfort and help when a person with dementia is in hospital, so check the visiting arrangements, and if you have any concerns discuss these with the ward manager. Many hospitals are signed up to John’s Campaign, which welcomes unrestricted visiting for family carers of people with dementia.

Between visits, or if you cannot visit, you might be able to keep in touch by phone or video call. The hospital may also have a befriending service to provide the person with company when they have no visitors.

Try to build a good relationship with the ward staff so you can stay informed about the person’s care. It is often best to arrange a time to meet, rather than dropping in when they are not expecting you. If you cannot visit regularly, find out if there is a good time to phone the ward for updates.

Ask to be kept informed if there are any changes to the person’s condition or treatment. The dementia team or Admiral Nurse may also be able to liaise with the medical team and pass on any updates.

Many people with dementia like to walk around and become agitated if they cannot do so. Ask the staff if it is safe and possible for the person to walk around the ward or visit the day room. They may be able to leave the ward with a visitor to go the hospital café or grounds.

Make sure the hospital knows if the person is prone to falls, which may be more likely if they are unwell and in an unfamiliar environment. Hospital staff may use monitoring equipment like a fall alert mat or chair sensor to alert them if the person gets up or falls so they can provide support.

To ensure the person with dementia eats and drinks as well as possible during their admission, tell staff about their food and drink preferences, and record these in their care passport.

Picture menus may be available to help the person choose their meals. Lighter, snack or finger food menus may be offered for people with smaller appetites. If the person has difficulty using cutlery, ask if adapted or ‘easy grip’ cutlery is available.

Some hospitals allow carers to visit at mealtimes to support the person with eating. They may also use a ‘red tray’ scheme or a sign above their bed to highlight which patients need extra assistance.

If the person has difficulty swallowing, they can be assessed by a speech and language therapist who can provide advice. If there are general concerns around their eating and drinking, a dietitian can offer support.

Delirium is a state of sudden, intense confusion that may occur when someone is unwell. It is a common condition in hospital, especially in people with dementia. It is sometimes known as ‘hospital related delirium’ and can appear to make someone’s dementia worse.

Signs of delirium include:

Delirium is treated by addressing the underlying cause, such as an infection or dehydration. It can some time to resolve, even after the cause is treated. In the meantime, the person may need extra support and reassurance.

Some families have reported concerns about people with dementia not being adequately supported in hospital with going to the toilet. This can lead to a lack of dignity and loss of long-term continence. These tips may help:

If the person has problems with incontinence, make sure staff are informed, including how their difficulties are usually managed (eg do they use pads or a full brief? How often do they need to change?).

If you notice any problems with how the person’s continence is being managed, please talk to ward staff.

If a person with young onset dementia (where symptoms develop before the age of 65) is admitted to hospital, it is very important to make sure ward staff are aware of their diagnosis, as they may not expect a younger person to be living with dementia. Younger people are also more likely to have rarer forms of dementia that staff are unfamiliar with, so ensure they understand how the person’s condition affects them and what support they need.

Many younger people with dementia will benefit from having their mobile phone or tablet with them, but be aware that valuables sometimes go missing in hospital. Inform the ward staff that the person has them, and if possible, set up face or fingerprint recognition and device tracking. Make sure the person has chargers and headphones.

If the person has children who would like to visit, find out if this can be accommodated. If they cannot visit the ward, ask if there is an alternative space where they could meet, like a café or outdoor area. This may also be less stressful for the child.

If you have a concern about the person’s care, talk to their named nurse in the first instance, who may escalate it to the nurse in charge. If you are not satisfied with their response, you could ask to speak to the ward manager. The Admiral Nurse or dementia team may also be able to help.

Try to stay calm and be specific about your concern, for example: “On two occasions the person’s meal was taken away before they had finished.” Be clear about how they can resolve your complaint. It is helpful to write a record of what is said and done.

If you remain concerned, you could contact the hospital’s Patient Advice and Liaison Service (PALS), which supports patients and families in resolving problems.

When a person is in hospital, important decisions may arise relating to their health and care. If the person with dementia has capacity to make decisions, they can do so themselves, with support if needed.

If the person lacks capacity but has a lasting power of attorney (LPA) for health and welfare (power of attorney in Scotland), their nominated attorney can make certain decisions on their behalf. You should ensure the hospital knows that they have an LPA.

If the person with dementia has not made an LPA and a decision needs to be made about their treatment, a ‘best interests decision’ may be made in consultation with the medical staff, the person themselves (if possible) and their family and/or other people close to them.

The person with dementia may also have:

If the person has these, you should give copies to the hospital.

DNACPR stands for ‘do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation’. If a person has a DNACPR agreement, their medical team will not try to restart their heart if it stops.

It is possible that a doctor may recommend the person with dementia has a DNACPR, especially if they are frail and in poor physical health. This can come as a shock, but CPR is rarely successful and can lead to unnecessary suffering at the end of life.

The person with dementia (if they have capacity) and their family members should always be involved in deciding whether they should have a DNACPR, but ultimately, the decision rests with their healthcare professionals if they feel it is in the person’s best interests.

A DNACPR only applies to resuscitation – the person with dementia will still receive all the other health treatment and care support they need.

When the person is ready to leave hospital there will be a discharge planning process to develop a plan that considers their needs, where they will be living and who will provide care or support. This should involve you, the person themselves if possible, and the professionals involved in their health and social care.

It is important to talk to hospital staff about the discharge plan and raise any concerns. It may help to make a list of who you have spoken to and their contact details.

Social Services should also carry out a carer’s assessment (for you) and needs assessment (for the person with dementia) to establish what support you will both need. If possible, any adaptations to help the person live safely at home should be in place prior to discharge, for example grab rails, toilet frames or hoists.

The person’s discharge plan should be reviewed in the community to ensure that it continues to meet their needs.

If the person with dementia is nearing the end of their life in hospital, they and their family and friends will usually be supported by a palliative care team, who will ensure they are kept comfortable and receive person-centred care tailored to their needs and preferences. The palliative care team can also help with the person’s discharge plan or help to arrange transfer to a hospice, community hospital or care home.

To speak to a dementia specialist Admiral Nurse about a stay in hospital or any other aspect of dementia, call our free Helpline on 0800 888 6678 (Monday-Friday 9am-9pm, Saturday and Sunday 9am-5pm, every day except 25th December) or email helpline@dementiauk.org

If you prefer, you can pre-book a phone or video call appointment with an Admiral Nurse: visit dementiauk.org/book

Our free, confidential Dementia Helpline is staffed by our dementia specialist Admiral Nurses who provide information, advice and support with any aspect of dementia.

Nat reflects on her experience of being a young carer and the support she received from the Nationwide dementia clinic.

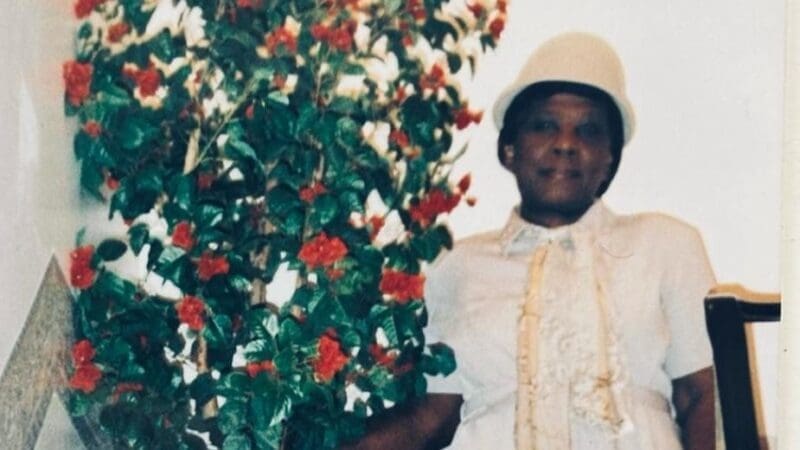

Tim reflects on the stigma that is often attached to dementia and the importance of the Black, African and Caribbean Admiral Nurse clinics.

Katrina reflects on the support she has received from her Admiral Nurse, Rachel, since her husband was diagnosed with young onset dementia.