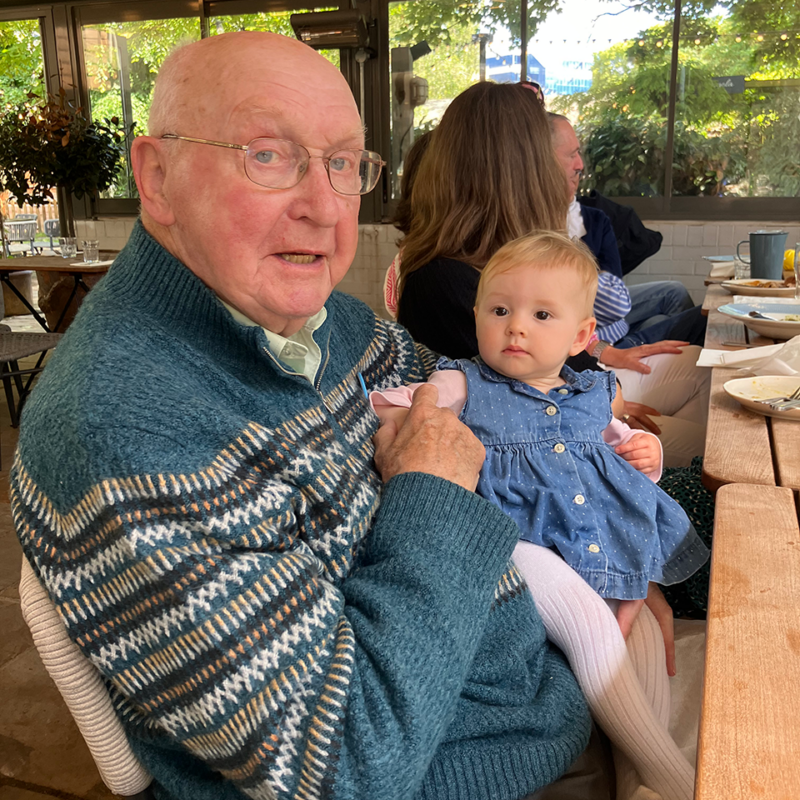

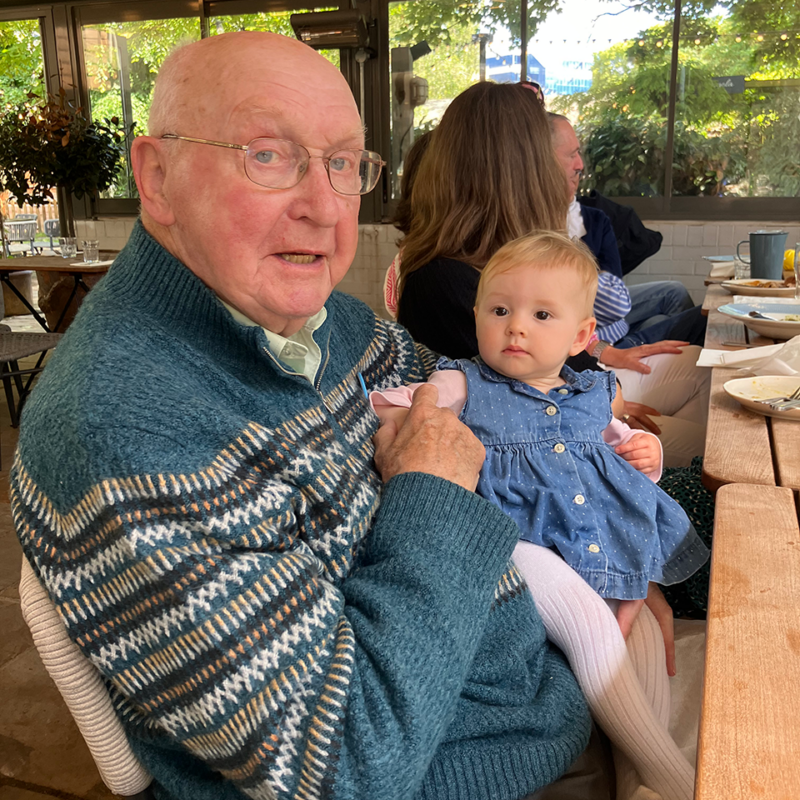

Caring for Dad, from near and afar – Simon’s story

Simon, who has lived in New Zealand for two decades, discusses how he cares for his dad who has Alzheimer’s disease and lives alone in the UK.

Mental capacity is a legal term that refers to whether someone is capable of making informed decisions. A person with dementia is likely to lose capacity over time, so it is important to know what to do in this situation.

Because dementia is a progressive condition, most people with the diagnosis reach a point where they cannot make their own decisions, for example about their health, care, finances and living arrangements. This is called loss of capacity.

To have capacity, a person must be able to:

When a person loses capacity, family members, friends or professionals such as a doctor, social worker or solicitor may need to make decisions for them.

Capacity can fluctuate – for example, a person might lose capacity due to an illness like delirium (sudden, intense confusion) but regain it when they recover. They may also have capacity to make some decisions (eg what to buy from the shops) but not others (eg whether to sell their home).

As a family member, you can assess whether the person with dementia has capacity, but you must follow the Mental Capacity Act Code of Practice, which says:

You might have an opinion about whether the person is able to make informed and safe decisions, but this is not a legal assessment of capacity; and making a decision that you disagree with does not necessarily mean they lack capacity. You must have ‘reasonable belief’ that they lack capacity according to the Mental Capacity Act, and be able to objectively explain your reasons to anyone who queries it.

If you are in any doubt about a person’s capacity, you can ask a professional to carry out a formal assessment of mental capacity. This is particularly important for major decisions like whether the person should move into a care home or sell their own home.

A formal assessment of mental capacity can be carried out by a professional such as a GP, social worker for decisions about health or care; or a solicitor for legal or financial decisions. They must consider two questions:

A formal assessment of mental capacity only covers the specific decision being made at that time – eg whether the person should receive an immediate medical treatment. If there are further decisions to be made, each will need a separate assessment.

The professional carrying out the assessment should keep a written record of the assessment and outcome.

When someone is diagnosed with dementia, they should be encouraged to start planning for the future as soon as possible. If the person has only recently been diagnosed or has young onset dementia (where symptoms develop before the age of 65) this may not seem urgent, but it is impossible to predict how quickly their condition will progress. Considering future plans early will make managing their care and finances less complicated and ensure their wishes are considered if they later lose capacity.

These plans should include:

An advance care plan (ACP): this sets out the person’s wishes for their medical and personal care, including long-term care like moving into a nursing home. It is not legally binding but will help the people involved in the person’s care to make decisions in their best interests.

An advance decision: a legally binding document where a person decides to refuse certain medical treatments in the future if they cannot communicate their wishes at that time. It is also known as an advance decision to refuse treatment (ADRT) or a living Will and includes life-sustaining treatment like CPR, ventilation and antibiotics.

Lasting power of attorney (LPA): a legal process where the person appoints someone trusted to make decisions on their behalf. There are separate LPAs for health and welfare, and property and financial affairs. Without an LPA, you may not legally be allowed to make decisions on the person’s behalf – even if you are their next of kin. You may have to apply to the Court of Protection to become the person’s ‘deputy’, which can be a complicated process.

A Will: this ensures the person’s money and other assets like property are left to the people and causes of their choosing after their death. It can be very difficult to make or change a Will on behalf of someone who has lost capacity, so it is important for them to make their Will as soon as possible. Dementia UK has free Will-writing offers for anyone wishing to make or amend a Will.

If a person with dementia has lost capacity, other people may have to make decisions on their behalf in their best interests. A ‘best interest meeting’ should be arranged which includes the person themselves if possible, their family/friends, health and social care professionals and anyone else who is actively involved with supporting them. Family and friends can only legally make decisions if they have been nominated in the person’s LPA.

Every attempt should be made to find out the wishes of the person with dementia. If they have an ACP, this should be taken into account.

Best interests decisions should always be the least restrictive option possible. For example, if the person wishes to go out for walks but they are vulnerable and would be at risk, the least restrictive option would be for someone to accompany them, rather than deciding they cannot go out at all.

Some decisions, such as selling the person’s home or moving into residential care, can be very difficult and may cause disagreements with the person with dementia and/or family members. The best outcome is where everyone involved comes to a consensus about the best interests of the person with dementia.

Where there is a dispute, the person can access an independent mental capacity advocate (IMCA) to support them to communicate their wishes.

Deprivation of liberty refers to a person having their freedom restricted for their own safety and being under continual supervision and control – for example in hospital or a care home. Deprivation of Liberty Safeguards (DoLS) ensure that the restrictions are appropriate and proportionate.

It is only legal to deprive an individual of their liberty by placement in a care home or hospital if:

Before someone is deprived of liberty, a mental health assessor must check if they lack capacity. They and a best interests assessor (usually a social worker, nurse, psychologist or occupational therapist) will then discuss whether deprivation of liberty is in the person’s best interests. The outcome can be challenged by anyone who feels the decision is wrong.

To speak to a dementia specialist Admiral Nurse about capacity and decision-making or any other aspect of dementia, please call our Helpline on 0800 888 6678 (Monday-Friday 9am-9pm, Saturday and Sunday 9am-5pm, every day except 25th December) or email helpline@dementiauk.org.

Alternatively, you can book a phone or video appointment in our virtual clinic.

Our free, confidential Dementia Helpline is staffed by our dementia specialist Admiral Nurses who provide information, advice and support with any aspect of dementia.

Simon, who has lived in New Zealand for two decades, discusses how he cares for his dad who has Alzheimer’s disease and lives alone in the UK.

Janet shares her experience caring for husband Ben and how they maintained the joy of Christmas after his diagnosis.

Shara reflects on her journey caring for Anna, her mother, who was diagnosed with vascular dementia in 2016.