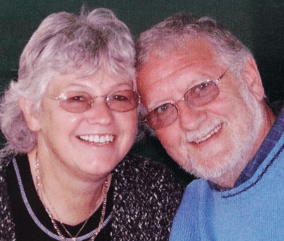

I still cherish every moment I have with Jan – Bob’s story

Bob, who has been married to Jan for 62 years, reflects on their beautiful relationship in spite of a heartbreaking journey with dementia.

When someone is diagnosed with dementia, it is natural to experience a range of emotions. For some people, this develops into persistent depression or anxiety – and it is important that they get support.

Depression is a state of low mood that lasts for weeks or months and interferes with a person’s everyday life.

Symptoms include:

Depression can also cause physical symptoms, including:

Anxiety is a feeling of fear or unease. Everyone feels anxious at times, but it can become so intense that it gets in the way of everyday life.

Symptoms include:

Physical symptoms include:

It is often assumed that people with dementia do not experience depression or anxiety but that is not the case.

Reasons for depression or anxiety in a person with dementia may include:

Mood changes can also be a symptom of some forms of dementia, such as vascular dementia and Lewy body dementia.

People with dementia may have difficulty expressing that they are feeling anxious or depressed. However, there may be clues in their behaviour, for example:

Because of the similarity in symptoms, dementia is sometimes misdiagnosed as anxiety or depression, which may delay an accurate diagnosis.

This can be a particular issue for people who develop dementia symptoms before the age of 65 (known as young onset dementia), as some healthcare professionals lack awareness of dementia in younger people and how it presents.

Similarly, depression or anxiety may be overlooked in a person with dementia as the symptoms may be put down to their dementia.

Depression-related psychosis may also be missed, as symptoms such as hallucinations and delusions may occur in dementia – particularly Lewy body dementia.

If low mood or anxiety are affecting someone’s daily life, it is important that they seek help.

If possible, support the person to take a self-assessment quiz first.

It is also useful to keep a symptom diary – family members and friends could contribute to this too.

The GP should ask the person about their symptoms and:

It is helpful for a family member or friend to go to the GP with the person to offer support and provide information about any changes they have noticed.

A GP can usually make a diagnosis of anxiety or depression based on what the person tells them. They may also take blood tests to rule out conditions with similar symptoms, such as thyroid problems or vitamin deficiency.

For many people, the symptoms of mild to moderate anxiety or depression can be eased without medical treatment. The following may help:

Generally, these strategies are more effective in the early to middle stages of dementia – people in the later stages may find it hard to engage with them.

In some cases – for example, if the strategies above have not helped or the person’s anxiety or depression are more severe – medication such as antidepressants may help. These may also be prescribed for the symptoms of frontotemporal dementia.

If you support a person with dementia who is experiencing anxiety and/or depression, these tips might help:

To speak to a dementia specialist Admiral Nurse about depression, anxiety or any other aspect of dementia, call our free Dementia Helpline on 0800 888 6678 (Monday-Friday 9am-9pm, Saturday and Sunday 9am-5pm, every day except 25th December), email helpline@dementiauk.org or you can pre-book a phone or video appointment with an Admiral Nurse.

Mental health support groups and services

Professional bodies for finding registered therapists and counsellors

Our virtual clinics give you the chance to discuss any questions or concerns with a dementia specialist Admiral Nurse by phone or video call, at a time that suits you.

Bob, who has been married to Jan for 62 years, reflects on their beautiful relationship in spite of a heartbreaking journey with dementia.

Julie Hayden was diagnosed with dementia at just 54 years old. She's since dedicated herself to advocating for people living with dementia and elevating the voice of lived experience.

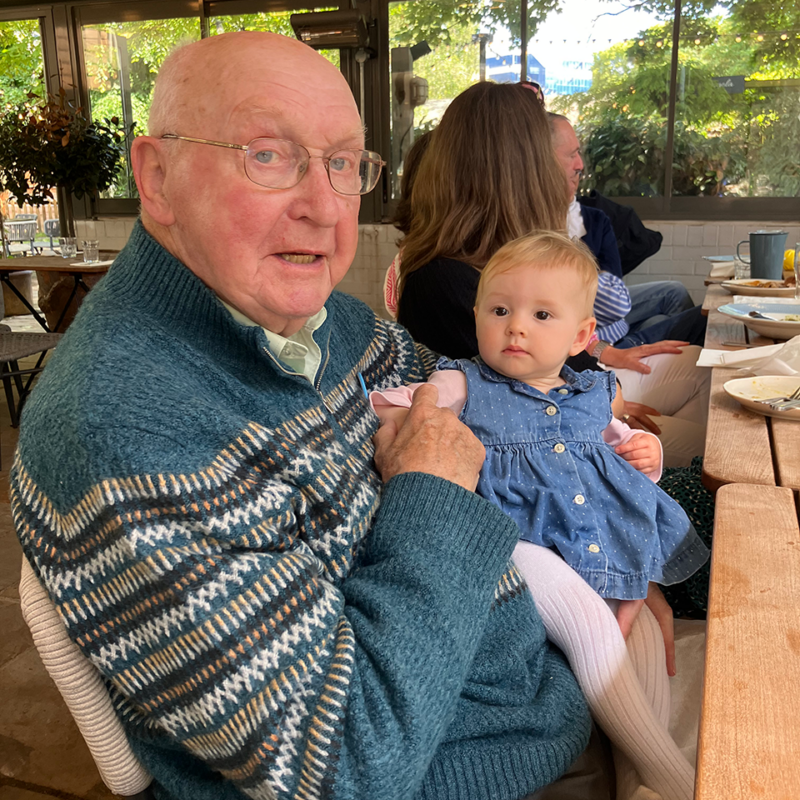

Simon, who has lived in New Zealand for two decades, discusses how he cares for his dad who has Alzheimer’s disease and lives alone in the UK.