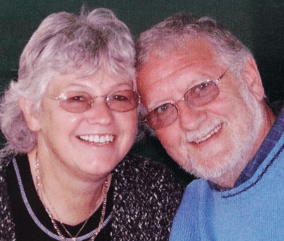

I still cherish every moment I have with Jan – Bob’s story

Bob, who has been married to Jan for 62 years, reflects on their beautiful relationship in spite of a heartbreaking journey with dementia.

Stigma and discrimination can have a significant impact on how a person with dementia is treated. We explain how this may affect them, and ways to cope.

When someone is diagnosed with dementia, they may feel a sense of stigma or discrimination, with people treating them differently, or sometimes even badly.

Stigma is a negative or unfair belief based on a stereotype about a person – such as their age, race, religion, gender, sexual orientation or disability, for example, “People with dementia cannot live independently.”

Discrimination is unfair treatment that results from the negative stereotype, for example, the person’s performance at work may be called into question.

Stigma and discrimination against people with dementia often result from a lack of understanding about the condition. People might not realise that certain changes are due to the person’s dementia and blame them for the way they are behaving.

For instance, if there are communication difficulties that make it difficult for the person to follow instructions, other people may think they are being uncooperative and become frustrated with them.

Or they might be finding personal care difficult, leading to family members being embarrassed to be seen with them in public.

Other causes of stigma and discrimination against people with dementia include:

Sometimes, people with dementia feel stigma towards themselves – for example, they might think they are ‘stupid’ or ‘a burden’ due to their diagnosis. This is called self-stigma.

People with young onset dementia (where symptoms develop before the age of 65) may face significant stigma and discrimination.

In the early stages, memory loss is often less of a problem, but the person may have other difficulties that make people see them less favourably, for example:

In addition, many people assume dementia does not affect younger people, so they may not realise that the changes in behaviour are linked to dementia and think the person is being ‘difficult’, ‘unreliable’ or ‘unpredictable’.

For example, if the person shows reduced empathy and unstable emotions, their family might believe that they are being unkind or unfair, particularly if this affects their behaviour with their children.

Stigma and discrimination around dementia can be a particular issue for people from minority ethnic communities. This might result from:

Negative stereotypes can have many consequences for a person with dementia, including:

A person with symptoms of dementia might be reluctant to seek a diagnosis because they are afraid of how they might be treated once they’re diagnosed.

This can lead to delays in getting assessed and diagnosed, sometimes for years – time in which they could have received treatment and support.

It may also mean that they don’t seek help for other treatable conditions that have similar symptoms – like certain infections, vitamin or hormone deficiencies, mental health issues and stress – because they are afraid they will be diagnosed with dementia.

Some people with dementia and their families feel ashamed of the diagnosis because of the potential for stigma and discrimination. They may end up withdrawing from socialising and their usual activities, which can contribute to loneliness and isolation.

Sometimes, family and friends behave differently towards the person with dementia. This may be due to fear, negative stereotypes, or worries about saying or doing the wrong thing.

For example, they may become overprotective of the person, believing that some things they can still do may now be too risky. However, there’s plenty of evidence to suggest otherwise – and that continuing to be as independent as possible and do the things they enjoy is beneficial for the person’s wellbeing.

Under the Equality Act and the Disability Discrimination Act, people with dementia have a legal right to be protected from discrimination:

Workplace discrimination can be a particular problem for people with young onset dementia (dementia in people aged 65 and under), who may be treated unfairly because of their diagnosis – eg denied promotion, put on probation or even dismissed/put under pressure to retire early.

If the person with dementia feels they have been discriminated against, they can:

For more information about taking action against discrimination in general, you can contact the Equality Advisory Support Service.

For advice on discrimination at work, read our information on employment and dementia, or contact Acas.

If you have any questions or concerns relating to dementia, call our free Dementia Helpline on 0800 888 6678 (Monday-Friday 9am-9pm, Saturday and Sunday 9am-5pm), email helpline@dementiauk.org or you can book a virtual appointment with an Admiral Nurse via phone or video call.

Our free, confidential Dementia Helpline is staffed by our dementia specialist Admiral Nurses who provide information, advice and support with any aspect of dementia.

Bob, who has been married to Jan for 62 years, reflects on their beautiful relationship in spite of a heartbreaking journey with dementia.

Julie Hayden was diagnosed with dementia at just 54 years old. She's since dedicated herself to advocating for people living with dementia and elevating the voice of lived experience.

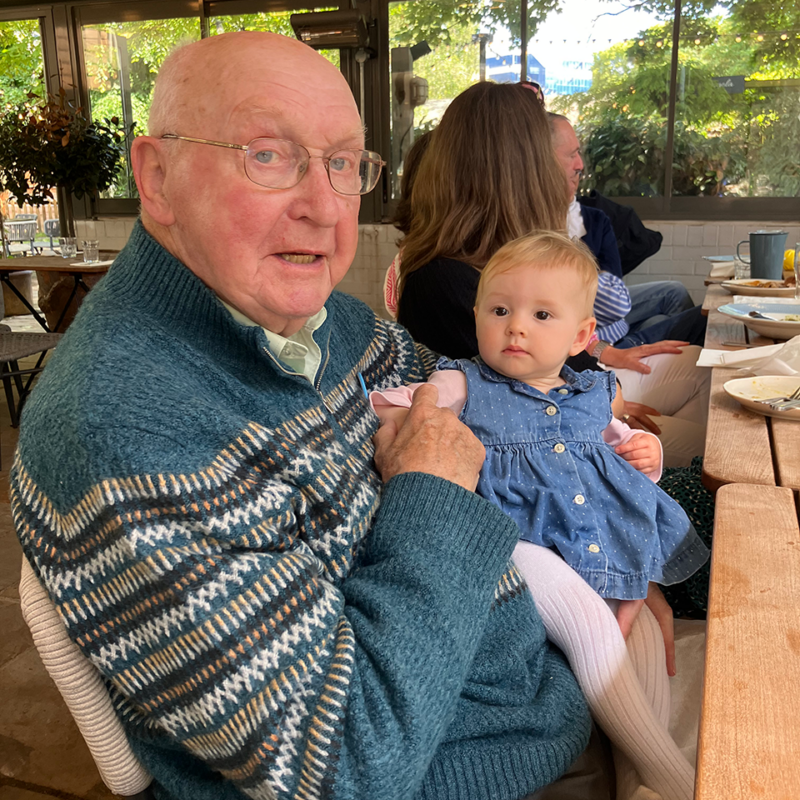

Simon, who has lived in New Zealand for two decades, discusses how he cares for his dad who has Alzheimer’s disease and lives alone in the UK.