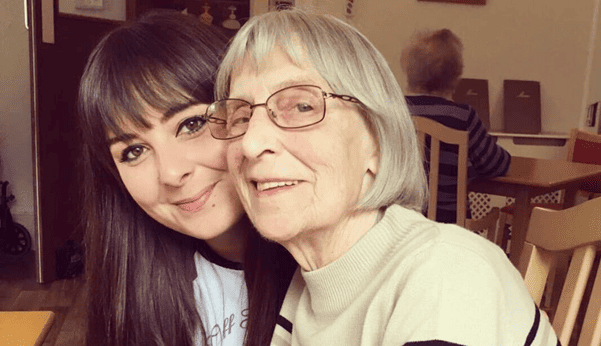

Peter’s story

Peter shares why he and his puppy Murphy, will be taking part in Dementia UK's 10k Lapland Dash.

Dementia is a progressive condition, and everyone with the diagnosis will die with or from it. Understanding the changes that happen in the last days can help you feel more prepared for what to expect.

Everyone experiences dying in their own way, with their own individual needs. However, certain changes commonly occur as someone approaches the end of life, which can alert you to the fact that they are nearing death.

These include:

When someone is dying, their body no longer has the same need for food and drink. Their metabolism slows down, and they become less able to digest food or absorb the nutrients from it. Interventions like a feeding tube or drip are unlikely to extend their life and may cause distress and discomfort.

This can be hard to accept, and you may feel you should persevere with encouraging the person to eat and drink, but these changes are a natural part of dying. Rather than focusing on how much the person is eating and drinking, it is better to offer food and drink simply for pleasure and enjoyment. For example:

The process of ‘withdrawal from the world’ tends to be gradual. People often seem calm and peaceful when they are awake, but show less interest in what is going on around them.

As they near death, they usually become increasingly sleepy. Most people eventually slip into unconsciousness and die peacefully and quietly in their sleep.

To bring the person comfort:

Breathing can slow down and become shallower as the body becomes less active. People may also develop an irregular breathing pattern or a noisy rattle to their breathing. This is caused by a build-up of mucus in the chest, which they are unable to cough up.

In the final stages, their breathing pattern may change again, with long pauses between breaths. Also, the abdomen may rise and fall instead of the chest.

If you’ve experienced breathlessness yourself, you may be worried that the person is frightened and fighting for breath, but it is not thought that breathing changes at the end of life cause distress.

Occasionally, people become more agitated as death approaches. If this happens, healthcare professionals can give medication to help control pain and other symptoms.

The person’s skin may become pale, moist and slightly cool prior to death. You may see changes in the colour of their hands, feet, fingernails and toenails as the body becomes less able to circulate blood.

Some people who are close to death experience hallucinations, for example seeing or hearing things that are not really there. If they are distressed by hallucinations, sedative medication may be given.

Some people may be given ‘anticipatory medications’ by health or care professionals. These are used to make them more comfortable, and include medication to relieve pain, soothe anxiety, reduce nausea or sickness, and ease the noisy breathing caused by excess mucus.

Sedation may also be given to reduce any distress.

When people need to have medication frequently, they may be given a syringe driver. A small needle is inserted under the skin, and a measured, continual dose of medication is delivered by a battery-operated pump.

A syringe driver will be managed by a nurse, and reduces the need for repeated injections.

It is important to think about where the person should be cared for at the end of their life.

Many people would prefer to die at home. If the person is in hospital, speak to staff about whether it is possible for them to be discharged home with support from palliative care nurses.

If the person lives in a care home, talk to their carers about whether they should be moved to hospital if their health deteriorates, or whether they can be monitored and supported in the care home to avoid the stress of going into hospital.

Some people are referred to a hospice at the end of their life. However, this does not necessarily mean they will be admitted to the hospice and die there – it is more common for a hospice nurse to visit them at home and support them to have a comfortable and dignified death.

When someone you are close is approaching the end of life and eventually dies, it’s natural to need time and support.

If the person is in a hospital or care home, staff should be able to keep you updated on their condition, advise you of any practicalities that might make things less stressful – such as an exemption from hospital car parking charges if you are visiting for long periods – and contact you when they feel death is imminent and you should be with them.

If they are at home, a district nurse, hospice nurse or GP may be able to explain what is happening and offer you support themselves or point you towards support groups in your area.

Our specialist dementia nurses are also available to support you on our Helpline or in clinics: please see Sources of support, below, for contact details.

Children and young people may need support to understand the dying process, especially if a parent with young onset dementia (where symptoms develop by the age of 65) is nearing death.

You can speak to a GP or social worker about bereavement support for young people, contact our Helpline or clinics, or contact the charity Child Bereavement UK.

To speak to a specialist dementia nurse about understanding dying or any other aspect of dementia, please call our free Dementia Helpline on 0800 888 6678 (Monday-Friday 9am-9pm, Saturday and Sunday 9am-9pm, every day except 25th December), email helpline@dementiauk.org or you can book a phone or video appointment.

Our virtual clinics give you the chance to discuss any questions or concerns with a dementia specialist Admiral Nurse by phone or video call, at a time that suits you.

Peter shares why he and his puppy Murphy, will be taking part in Dementia UK's 10k Lapland Dash.

Jen, who works at tails.com, explains why she took on the October Dog Walking Challenge for Dementia UK.

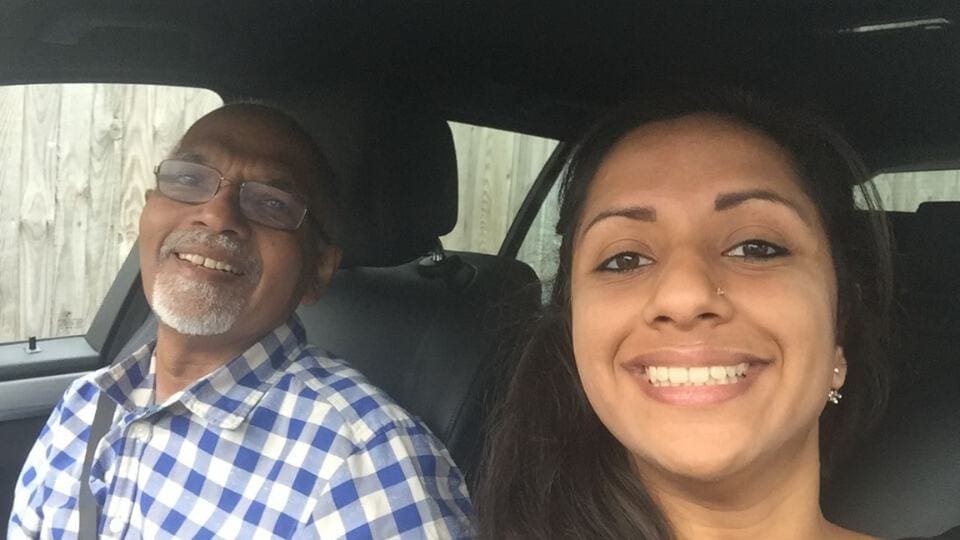

Eshaa shares how young onset dementia impacted her father's capabilities to communicate with his friends and family.