“The lack of recognition of unpaid carers is frustrating”

Will shares how his mum's diagnosis impacted the family and highlights the importance of advocating for young carers.

Our specialist nurses share tips and advice to help parents support children and adolescents when the other parent has young onset dementia.

Many people living with young onset dementia have young or adolescent children who will experience the impact of dementia first hand.

As a parent, if you are caring for a partner with young onset dementia and looking after children too it can be a stressful and socially isolating time for you.

Juggling these dual caring responsibilities along with work, finances, the home and wider family life can be very challenging. You may feel torn between your needs and those of your partner and children.

Witnessing changes in a parent can be very upsetting for a child or teenager, especially if they do not understand what is happening.

It can be helpful to describe dementia to them as a journey: as the condition progresses, each stage of the journey is different, and can affect individuals in different ways.

Often, dementia is associated with memory loss, but people with young onset or rare dementias may experience different symptoms, such as changes in:

Over time, the person with dementia may need more help with everyday things. Be honest with your child about these changes and prepare them for the fact that their parent will not get better.

Children and adolescents express their emotions in a variety of ways. They may be aware that family relationships are changing, causing them anxiety, stress and feelings of loss or grief.

You may notice changes in their mood, behaviour and emotions or their schoolwork may be affected. They may also show physical responses such as headaches, nausea and complain of aches and pains.

Over time, the parent with dementia will become less able to engage with and care for their child. This can lead to a role reversal where the child needs to take on a caring role for their parent.

You may have less time and attention to dedicate to your children than you would like. These tips may help:

Your child may not consider themselves to be a ‘carer’ but if they provide practical, physical, emotional or personal care such as helping with cleaning, looking after siblings or helping their parent to eat meals, they are helping in a caring capacity.

Your child has certain legal rights in their caring role. Your local council has a duty to look at what responsibilities your child is taking on and assess if they need extra support. The NHS has more information on young carers’ rights.

Being a young carer can have a major impact, particularly on an teenager’s health, social life and self-confidence. Many young carers struggle to juggle their friendships, education and caring responsibilities.

Your child’s teacher, and the leaders of any sports or activity clubs they attend, should be made aware of the situation at home so support can be provided, if needed.

Some schools include dementia on their curriculum. If this is not the case in your child’s school, it might be useful to ask a teacher to have a short session about dementia, particularly if other children have a relative with the condition.

For younger children, there are illustrated books available about dementia that can help them to understand the condition in an age-appropriate way.

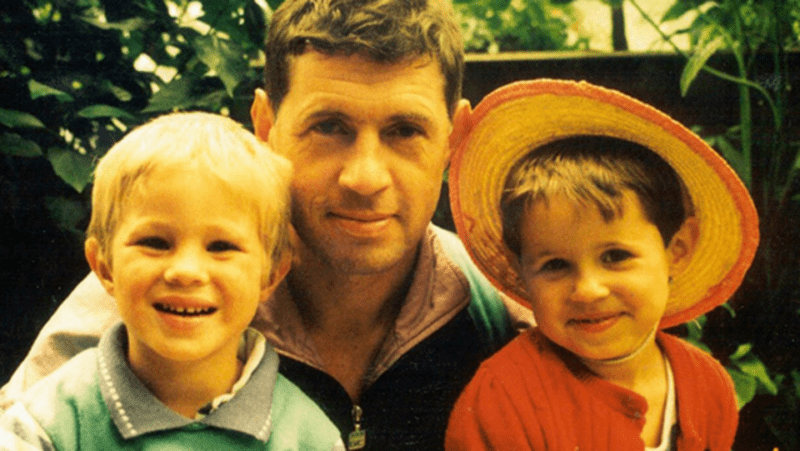

Try to make time to help your child create memories that they can cherish of time spent with their parent. If possible, arrange days out, a holiday or a short break so the whole family can create lasting memories.

Do not be afraid to ask family and friends to help with looking after the person with dementia so your child can have one-to-one time with you, or so you can attend special events like school plays and sports days.

If your child is older, encourage and support them to plan for their own future without feeling guilty, especially if this involves leaving home for university or work. Keep them up to date about the situation at home so that when they visit, they are prepared for what to expect.

Dementia is a life-limiting condition and anticipatory loss can happen long before the person dies.

In time, their parent may have to move into residential care or a nursing home. This will have a significant impact on your child and their home life – they may need extra support to come to terms with the change.

Losing a parent is a traumatic event and children can react to grief and bereavement in different ways, depending on their personality and age.

It is important for the child to feel loved, and for those around them to show compassion and understanding. Talk openly about the parent to allow the child’s positive memories to live on and keep photos and mementoes around the house to remember the person by.

Younger people with dementia are more likely to have a familial or inherited form such as young onset frontotemporal dementia, Alzheimer’s disease and some rare dementias.

Genetic testing is available for people aged over 18 but a detailed background medical history needs to be established first, and counselling spanning several months will also be required.

If a person does have a genetic mutation, it means that their children will have a 50% chance of inheriting the faulty gene and developing dementia in the future. A diagnosis of a genetically inherited form of dementia in a parent will therefore have repercussions.

If you need advice on any aspect of dementia, including young onset dementia, please call the Dementia Helpline on 0800 888 6678 (Monday-Friday 9am-9pm, Saturday and Sunday 9am-5pm, every day except 25th December), email helpline@dementiauk.org or you can also book a phone or virtual appointment with an Admiral Nurse.

Our virtual clinics give you the chance to discuss any questions or concerns about dementia, including young onset dementia, with a dementia specialist Admiral Nurse by phone or video call, at a time that suits you.

Will shares how his mum's diagnosis impacted the family and highlights the importance of advocating for young carers.

Chloe shares her experience of being a young carer for her Mum, who was diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia at 47, and died aged 51.

Helen reflects on her dementia journey and grief after husband Clive died from frontotemporal dementia in 1999.