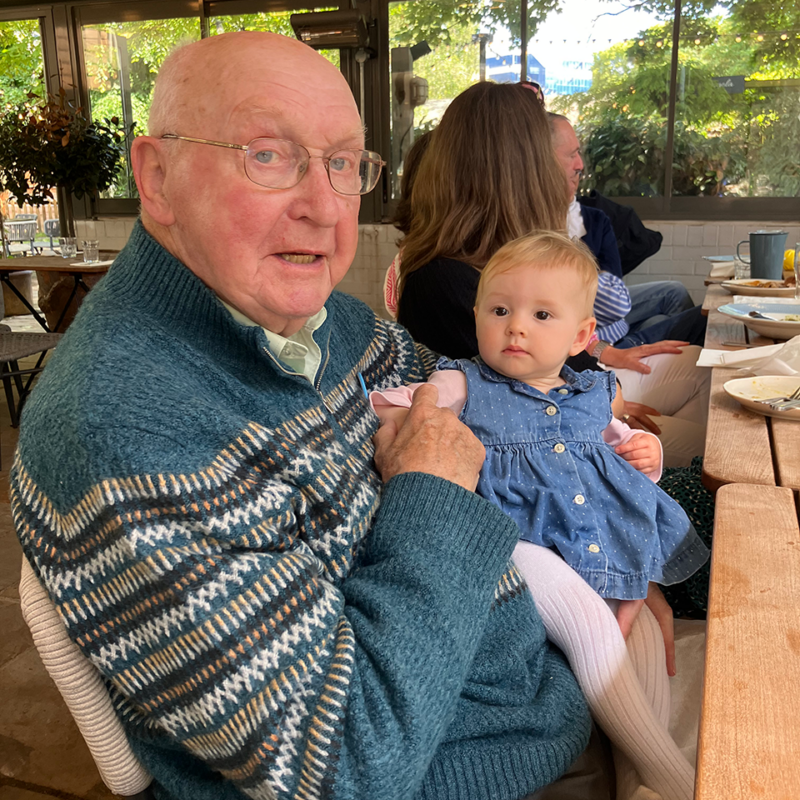

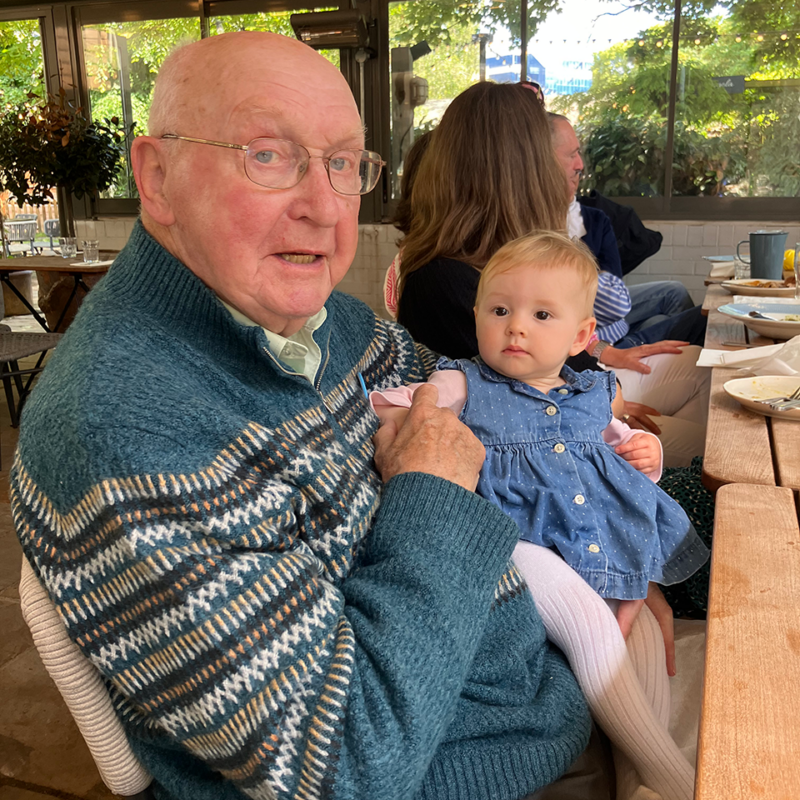

Caring for Dad, from near and afar – Simon’s story

Simon, who has lived in New Zealand for two decades, discusses how he cares for his dad who has Alzheimer’s disease and lives alone in the UK.

Delirium is common in people with dementia and can make them increasingly confused and distressed. Here, we explain the signs to be aware of and how you can help.

Delirium is a state of mental confusion that comes on suddenly. It can have a big impact on the way a person behaves and functions, especially if they have dementia.

People with delirium typically become confused and/or disorientated, and have difficulty concentrating.

There are two types of delirium:

Delirium can be very distressing for the person experiencing it and their carers.

Possible causes of delirium include:

Dementia can make people more likely to experience delirium. People who are over 80 and live with dementia are at greater risk, particularly during a hospital stay, when up to 50% of people with dementia develop delirium.

Older people with delirium and dementia often need longer stays in hospital, are more prone to falls or accidents, and are more likely to be moved into a care home.

It can be difficult to recognise delirium in people with dementia because it has similar symptoms such as confusion, memory loss and problems with concentration. However, it’s important to know the signs and seek medical help quickly if you spot them.

Symptoms of delirium include:

Delirium can be serious, so it’s vital that the person receives medical assistance as soon as possible.

If the person is at home, contact their GP and ask for an urgent appointment. If they are in hospital, tell the nurse or doctor who is looking after them. If they are in a care home, tell a carer.

If you think the person is seriously or suddenly unwell, take them to A&E or call 999 for an ambulance: in rare cases, delirium or its underlying causes can be life-threatening.

You could also try these ideas to try to ease the person’s distress:

If a person is experiencing delirium, their doctor should check for underlying causes, such as signs of infection like a high temperature.

They should ask you or the person whether they’re having problems with things like constipation or passing urine, and look at what medications they take.

They may also request blood and urine tests.

Often, delirium gets better if the underlying problem is treated. For example, if the person has an infection they may be prescribed antibiotics, or if they are constipated they may be given laxatives. Sometimes, there is no treatable cause of delirium; in these cases, the person may just need time and rest to recover.

If the person is particularly distressed, they may be given calming or sedating medication in the short term. However, for some people these medications make delirium worse, so they should only be used if absolutely necessary – for instance, if the person is at risk of harming themselves or someone else.

About 60% of people with delirium recover within a week. Some people, however, take longer to recover, and some never get back to exactly how they were before – this is more likely if they have dementia.

Delirium can’t always be prevented, but there are things you can do to reduce the risk.

If you have any questions or concerns about dementia, you can contact our free Dementia Helpline on 0800 888 6678 (Monday-Friday 9am-9pm, Saturday and Sunday 9am-5pm, every day except Christmas Day), email helpline@dementiauk.org or you can pre-book a phone or virtual appointment with an Admiral Nurse.

Our free, confidential Dementia Helpline is staffed by our dementia specialist Admiral Nurses who provide information, advice and support with any aspect of dementia.

Simon, who has lived in New Zealand for two decades, discusses how he cares for his dad who has Alzheimer’s disease and lives alone in the UK.

Janet shares her experience caring for husband Ben and how they maintained the joy of Christmas after his diagnosis.

Shara reflects on her journey caring for Anna, her mother, who was diagnosed with vascular dementia in 2016.