Nat’s story – “Being a young carer can be lonely”

Nat reflects on her experience of being a young carer and the support she received from the Nationwide dementia clinic.

For many people, driving is an important source of independence and enjoyment, so it is natural to worry that developing dementia will result in having to stop driving.

A diagnosis does not necessarily mean that someone has to stop driving immediately; however, dementia often impacts the skills involved in driving. The DVLA, or DVA in Northern Ireland, will decide whether a person with dementia can continue to drive.

On this page, our dementia specialist Admiral Nurses explain more about what the person with dementia needs to do after being diagnosed and how to support them, whether they can continue to drive or need to give up their licence.

When someone is diagnosed with dementia, they are legally required to inform the Driver and Vehicle Licensing Agency (DVLA – in England, Scotland and Wales) or the Driver and Vehicle Agency (DVA – in Northern Ireland).

It doesn’t automatically mean they will have to give up driving straight away, although this is possible.

Contact details to notify the DVLA Medical Enquiries:

Contact details to notify the DVA Medical Issues:

Once the relevant authority has been informed, it might make a decision immediately or:

They will then let the person know the outcome by letter. There are four possible outcomes:

If the person continues to drive when they have had to surrender their licence, they could be fined or prosecuted.

If the DVLA/DVA is not informed of a diagnosis, the person’s GP may disclose relevant medical information to the agency. This can be done without their permission but is best avoided if possible, as it can cause distress and resentment.

It is also a legal requirement to inform the person’s insurance company of their diagnosis. If not, their insurance will be invalid.

If the DVLA/DVA is unsure whether a person can still drive safely, they will ask them to take a driving assessment.

There are 20 approved driving assessment centres for this kind of assessment. They can also take place at a related ‘satellite centre’. The DVLA/DVA will refer the person to a location close to their home and pay for the assessment itself.

It is also possible to choose to have the assessment, particularly if the person with dementia wants some extra advice or teaching. To do so, they need to contact the centre directly and pay a fee. Prices vary, but they are between £70 and £90 on average.

The assessment isn’t the same as the one taken as a learner driver. It is carried out by a specialist occupational therapist and an advanced driving instructor who can assess the impact dementia is having on the person’s ability to drive safely. The person with dementia needs to bring their driving licence and glasses if they need them.

It is important to go to the appointment with another person who can drive or go home with them on alternative transport if they are deemed unsafe to drive.

The assessment is supportive in its approach and acknowledges some of the ‘bad habits’ that drivers may pick up over time. If the person can drive safely, the assessors will work with the driver to help them stay on the road.

The assessment takes around two hours and includes the following:

Being asked questions about their driving and medical history, as well as any problems they may have while driving. Then they will be asked to undertake a short written test.

Using a special static rig, both reaction times and limb strength will be tested. The rig is a car with a steering wheel and foot pedals that is linked to a computer to test these abilities. At this time eyesight will also be checked.

This will best show the person’s capabilities as the main part of the assessment. The test will take place in a dual-control car, meaning there is a brake on both the passenger and driver sides. To help the person get used to the test car, some centres have a private road so that they can drive around a little before while also allowing the instructor to check they are safe to be on a public road.

The next step is driving on a set route with the advanced driving instructor in the passenger seat, while the occupational therapist sits behind.

Once the assessment is completed, the assessor will explain their findings. If it is decided that the person can drive safely, they’ll get advice on how to do so confidently.

If the assessors decide that the person is not safe to drive, they will be informed of other options.

If the DVLA/DVA requests the assessment, the centre will send them a report. The licence holder can also request a copy.

The requirement to stop driving will depend on the person and their symptoms. In some cases, the person’s doctor will tell them they need to stop driving immediately if they are deemed unsafe on the road. If the doctor isn’t sure, more tests may be needed, and they will need to stop driving in the meantime.

Regardless of how long it takes for the DVLA/DVA to make a decision on whether someone can drive, it is important to follow medical advice.

If the person with dementia doesn’t inform the DVLA/DVA of their diagnosis, their GP may disclose relevant medical information to the agency. This can be done without their permission, but is best avoided if possible, as it can cause distress and resentment. The person with dementia could be fined up to £1,000 for not telling the DVLA/DVA about their diagnosis, and the person’s insurance may become invalid.

While many people who are diagnosed with dementia have been driving for a long time and feel confident, it is important to recognise that there are many factors to driving safely, which can become difficult as symptoms progress and have a greater impact on mental and physical abilities such as:

For a person with young onset dementia (where dementia develops before the age of 65) in particular, facing the prospect of not driving, whether that is by choice or because the person with dementia is told they can’t any more due to medical advice, can be especially difficult, especially as it can impact their job or ability to drive children around.

Finding support from those who understand their circumstances and can relate to what they are going through can be especially helpful: learn more about support groups and services.

Not everyone who has dementia will need to stop driving straight away. Deciding to continue to drive should be between the person, their GP, and those caring for them.

Some things can be done to increase confidence and maintain independence for as long as possible while driving, including:

If possible, go out in the car with the person at regular intervals so you can see if they are driving safely. If you believe they are no longer safe to drive:

Often, it’s better if the person with dementia stops driving voluntarily. This reduces the risk to them and others and allows them to feel more in control of what can be a difficult situation.

If the driver decides to surrender their licence, they need to inform the DVLA/DVA.

In England, Scotland and Wales they should use the Declaration of voluntary surrender for medical reasons form.

In Northern Ireland, they should send both parts of their driving licence and a cover letter explaining their condition to the DVA at the address above.

One of the most important things that you can do is support the person and acknowledge their feelings. While some will feel relieved, others will feel a huge sense of loss. Whatever they are feeling, listening and validating their feelings is a big step in offering support.

While it is against the law to keep driving if the DVLA/DVA has told them it is no longer safe to do so, some people will not want to. This can be worrying for their family, who may be wondering how to get someone with dementia to stop driving.

While it can be concerning, it is worth remembering that the person is not being difficult on purpose; their dementia could mean they can’t see how their symptoms are affecting their driving. The person may not remember that they no longer have a license or have not yet accepted their diagnosis.

If this is the case, the person’s family or doctor should write in confidence to the DVLA/DVA. The agency will be in contact with the local police.

Although it may feel difficult, supporting someone who is unsafe to drive but continues to try to is in their best interest.

Some ways that you may be able to help include:

When someone is diagnosed, they must tell their car insurance provider straight away. If they fail to do so, their insurance could be invalid. In the UK, it is illegal to drive without third-party insurance at a minimum.

To speak to a dementia specialist Admiral Nurse about driving or any other aspect of dementia, please call our free Dementia Helpline on 0800 888 6678 (Monday-Friday 9am-9pm, Saturday and Sunday 9am-5pm, every day except 25th December), email helpline@dementiauk.org or pre-book a phone or video call with an Admiral Nurse.

Our free, confidential Dementia Helpline is staffed by our dementia specialist Admiral Nurses who provide information, advice and support with any aspect of dementia.

Nat reflects on her experience of being a young carer and the support she received from the Nationwide dementia clinic.

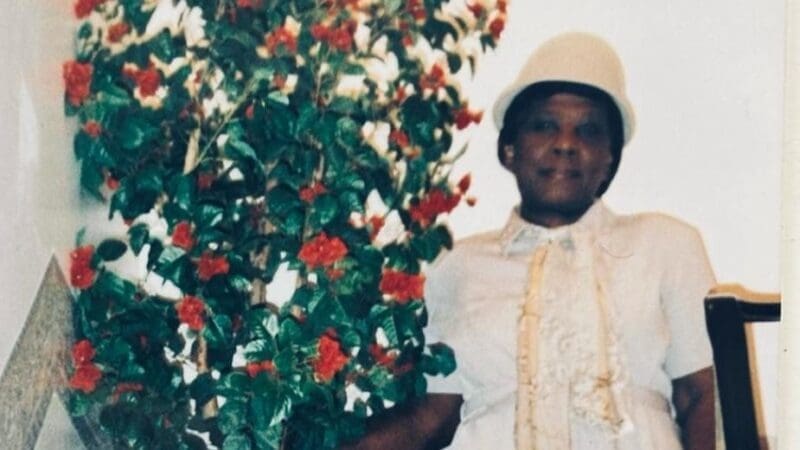

Tim reflects on the stigma that is often attached to dementia and the importance of the Black, African and Caribbean Admiral Nurse clinics.

Katrina reflects on the support she has received from her Admiral Nurse, Rachel, since her husband was diagnosed with young onset dementia.

Whether or not the person with dementia needs to be retested will depend on the decision of the DVLA or DVA. They will inform them of their decision.

A person with dementia may be entitled to a Blue Badge if they meet specific criteria. Find out more about the scheme, criteria and how to apply.

The Motability scheme depends on a range of criteria and assessments that will help understand how best to support a disabled person based on their individual needs. People with dementia can find out more about the scheme here.

The progression of dementia and certain early symptoms may mean a person’s ability to drive, and therefore, when they stop driving, may be impacted. This is particularly true of impulsive behaviour, which is common in frontotemporal dementia, and hallucinations that can be a part of Lewy body dementia.