Our Admiral Nurse helped start end-of-life talks

As a palliative care nurse, Jenny reflects on the importance of empathy during end of life care and how her Admiral Nurse helped her family prepare for her Mum's death.

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is an umbrella term for a group of dementias that mainly affect the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain, which are responsible for personality, behaviour, language and speech. Unlike other types of dementia, memory loss and concentration problems are less common in the early stages.

Frontotemporal dementia is a rare form of dementia affecting around one in 20 people with a dementia diagnosis.

On this page, our dementia specialist Admiral Nurses explain the symptoms and causes of frontotemporal dementia and possible treatment options.

Frontotemporal dementia usually develops between the ages of 45 and 65, whereas many other types are more common after the age of 65. In addition, frontotemporal dementia usually develops slowly, meaning that symptoms tend to increase over a longer period of time.

A person with frontotemporal dementia might have a range of symptoms, including changes in behaviour, cognitive difficulties and communication challenges.

Behavioural symptoms can include:

Cognitive symptoms can include:

Communication symptoms can include:

Motor symptoms can include:

When someone has frontotemporal dementia, they have an abnormal build-up of protein forming in clumps inside brain cells, which is thought to damage the cells and stop them from working the way they should.

These proteins build up in the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain, located at the front and sides, which are important for controlling behaviour, language and the ability to organise and plan.

Frontotemporal dementia often has a genetic link, meaning those who develop it also have relatives impacted by it.

It may be possible, if there is a family history, to have a genetic test to see if you’re at risk; you can talk to your GP about being referred to a geneticist.

It is possible for frontotemporal dementia to overlap with other neurological (nerve and brain) conditions, including:

There are a number of different types of frontotemporal dementia.

Behaviour variant frontotemporal dementia (bvFTD) is the most common type of frontotemporal dementia. A person with this type of dementia will experience symptoms that impact personality and mood.

Symptoms include:

There are three types of primary progressive aphasia (PPA), which all tend to affect language rather than behaviour.

As SD progresses, the changes are likely to become similar to those experienced in bvFTD.

Unlike in SD, people with early LPA are unlikely to forget the meaning of words or what common objects do.

Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) is a form of frontotemporal dementia. It affects around 4,000 people in the UK. It is caused by progressive damage to the cells in the brain that control eye movements.

PSP is characterised by difficulties with balance, movement, vision, speech and swallowing.

Because its initial symptoms can resemble other conditions such as Alzheimer’s disease or Parkinson’s, PSP can be difficult to diagnose.

For further information and support, visit the PSP Association website.

Corticobasal degeneration (CBD) is a frontotemporal dementia. It is a rare condition where brain cells become damaged over time and certain sections of the brain start to shrink. It is a progressive condition. This means that the initial symptoms will become more severe over time, and new symptoms may also develop.

Initial symptoms of CBD include

As the condition progresses, symptoms become more wide ranging and troublesome, such as

The PSP Association can offer support and information on CBD.

Due to a lack of education and awareness, it can be more difficult to get a diagnosis of frontotemporal dementia than some other forms. Reasons for this can include:

If you are concerned that someone may have frontotemporal dementia, it is important to encourage them to see their GP. If they are reluctant, you could contact the GP by phone, email or letter and outline your concerns – while the GP will not be able to breach the person’s confidentiality, they should consider the information and decide whether to call them in for an appointment or arrange a home visit.

If possible, go to the appointment with the person so you can share your views and concerns.

The GP should:

If the GP believes the person needs further investigations, they should be referred to a specialist in frontotemporal dementia for a comprehensive assessment of attention, memory, fluency, language, visuospatial abilities and behaviour changes. They may also have an MRI scan of the brain.

While there is currently no cure for frontotemporal dementia, there are treatments and strategies that may help manage some of the symptoms.

While medicines cannot stop the progression of frontotemporal dementia, there are some that can may help reduce symptoms such as a specific form of antidepressants called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which can help with symptoms such as compulsive behaviour, a lack of inhibitions or overeating.

In rare cases, a person may be prescribed antipsychotic medication if SSRIs have not worked, as they may help control behaviour that is putting the person or others around them at risk. However, antipsychotic medications should always be used with caution for anyone living with dementia, so the person’s doctor should carefully weigh up the risks and benefits.

The person’s current and future health and social care needs should be reviewed to create a care plan, to make sure they can access the right treatment and support. It can also identify areas where the person may need more assistance such as:

Read Chloe’s story about her experience of her mum’s frontotemporal dementia“The word ‘dementia’ didn’t even enter my mind. After all, Mum was in her forties. But after seeing a GP in 2018, she was referred to the memory clinic and diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia. Mum was 47 years old; I was 14.”

There is a range of therapies and other means of support that may be helpful to someone with frontotemporal dementia, such as:

Additional complications may arise for a person with frontotemporal dementia, particularly in the later stages, such as pneumonia, infections, increased risk of falls, and engaging in unsafe behaviours, including eating inedible items and wandering into traffic.

To speak to a dementia specialist Admiral Nurse about frontotemporal dementia or any other aspect of dementia, please call our free Dementia Helpline on 0800 888 6678 (Monday-Friday 9am-9pm, Saturday and Sunday 9 am-5pm, every day except 25th December) or email helpline@dementiauk.org. You can also book a video or phone appointment with an Admiral Nurse.

As a palliative care nurse, Jenny reflects on the importance of empathy during end of life care and how her Admiral Nurse helped her family prepare for her Mum's death.

Chloe shares her experience of being a young carer for her Mum, who was diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia at 47, and died aged 51.

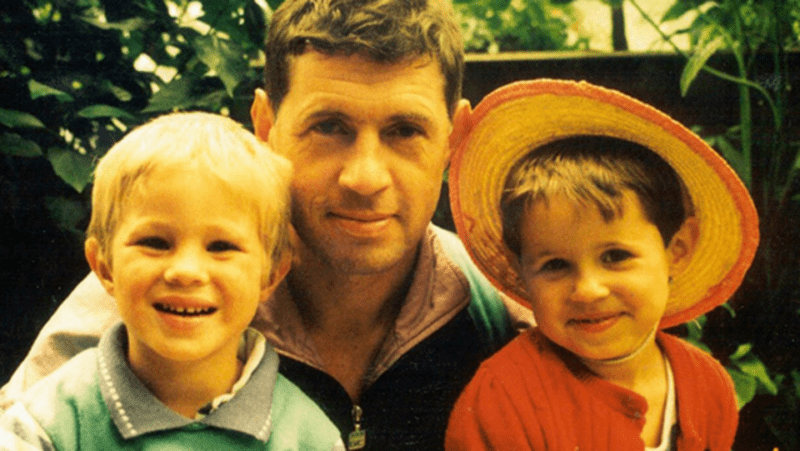

Helen reflects on her dementia journey and grief after husband Clive died from frontotemporal dementia in 1999.

While not specific to frontotemporal dementia, research suggests that there are things you can do to reduce the risk of dementia in general, such as keeping your mind active, eating a healthy and balanced diet, and taking regular physical activity.

There are currently no treatments to slow the development of frontotemporal dementia, so the focus is on learning strategies to manage its progression.