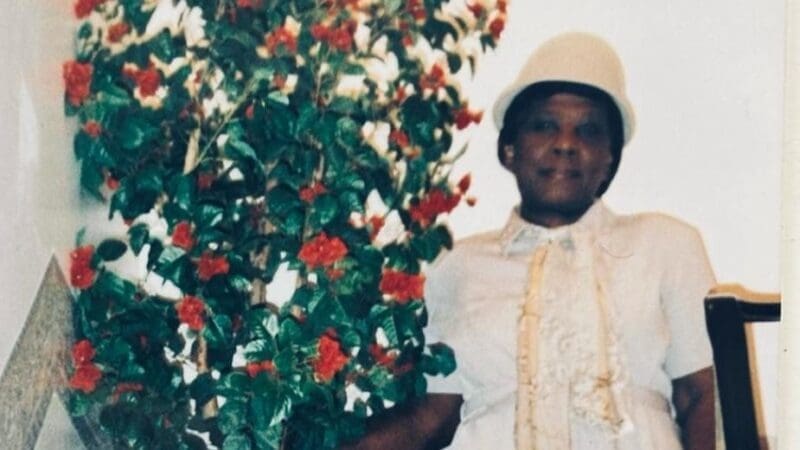

Nat’s story – “Being a young carer can be lonely”

Nat reflects on her experience of being a young carer and the support she received from the Nationwide dementia clinic.

Delirium is a state of sudden, intense confusion that can make people increasingly anxious, distressed and disorientated. Delirium is not the same as dementia, but it is common in older people and those living with dementia. Delirium is often triggered by treatable underlying causes such as infection, pain or dehydration, and is a serious medical issue that requires attention.

Our specialist Admiral Nurses explain the signs to be aware of and how you can help a person with dementia who is experiencing delirium.

Delirium is a state of intense mental confusion that comes on suddenly. It can have a big impact on the way a person behaves and functions, especially if they have dementia.

People with delirium typically become confused and/or disorientated and have difficulty concentrating. It can be very distressing for the person experiencing it and their carers.

There are three types of delirium: hyperactive, hypoactive and mixed. For older people, including those with dementia, hypoactive and mixed delirium are the most common.

Sometimes, delirium is described as ‘acute delirium’, however this is not a different type. Delirium is, by nature, acute, in that it comes on suddenly and often severely. It is sometimes referred to as ‘acute confusional state’.

Hyperactive delirium causes confusion that fluctuates throughout the day. A person who is experiencing hyperactive delirium may:

Hypoactive delirium is characterised by the person becoming less responsive. They may:

When someone is experiencing mixed delirium, they will have symptoms of both hyperactive and hypoactive delirium and may switch between them. A person with mixed delirium may be sleepy and unfocused one day, and agitated and restless the next.

It can be difficult to recognise delirium in people with dementia because many of the symptoms are similar: for example, confusion, memory loss and problems with concentration. However, it is important to know the signs and seek medical help quickly if you spot them.

The symptoms of delirium may be cognitive (affecting the person’s ability to remember, think and communicate), behavioural and/or physical. They include:

Older people with delirium and dementia often need longer stays in hospital, are more prone to falls or accidents, and are more likely to be moved into a care home.

Dementia

Delirium

Important to know

These differences apply to most people, but there can be exceptions. Dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB) can have symptoms similar to delirium. It may be hard to tell the difference without knowing how long symptoms have been present.

If you think the person is seriously or suddenly unwell, take them to A&E or call 999 for an ambulance: in rare cases, delirium or its underlying causes can be life-threatening.

Delirium is most common in older adults – particularly those over 80. There is also a strong link between delirium and dementia. Delirium is particularly common on hospital wards, affecting approximately 25-30% of older people and up to 50% of people with dementia. People living in care homes are also more prone to delirium.

There are a number of reasons why someone may develop delirium.

Medical conditions that can cause delirium include:

Environmental factors that can cause delirium include:

Some types of medication can make delirium more likely, especially if the person is taking multiple medications.

Up to 50% of older people who have surgery develop delirium. People who have hip surgery are at a particularly high risk, with research suggesting that 70-80% develop delirium.

Delirium is more common in people over 65; however, younger people can also be affected.

If a person is experiencing symptoms of delirium, it is important to seek medical advice. It can often be diagnosed based on their symptoms. Their healthcare professional should consider their:

The doctor may request blood and urine tests to check for underlying causes, such as an infection, constipation or difficulty passing urine. They should also review any medication that could be contributing to the delirium.

When a healthcare professional meets a person with dementia for the first time, it can be hard to tell the difference between dementia symptoms and delirium. This is why it is important to notice any sudden changes in the person’s behaviour and to ask for tests to check for health problems that can cause delirium.

Treating delirium usually involves addressing any underlying causes. For example, if the person has an infection, they may be prescribed antibiotics, or if they are constipated, they may be given laxatives.

Medication is not usually given for delirium itself. If the person is particularly distressed, they may be given a short, low-dose course of medication such as a sedative or antipsychotic. However, for some people, particularly those with Lewy body dementia, these medications can make delirium worse, so they should only be used if absolutely necessary – for instance, if the person is at risk of harming themselves or someone else.

Sometimes, there is no treatable cause of delirium; in these cases, the person may just need support, time and rest to recover, ideally in a calm and familiar environment. Family members can help by reassuring them that they are safe, making sure that they are wearing their glasses or hearing aids, and encouraging them to eat and drink.

Delirium can be serious, so it is vital that the person receives medical assistance as soon as possible if you notice the symptoms. If the person is at home, contact their GP and ask for an urgent appointment. If they are in hospital, tell the nurse or doctor who is looking after them. If they are in a care home, tell a carer.

If you think the person is seriously or suddenly unwell, take them to A&E or call 999 for an ambulance: in rare cases, delirium or its underlying causes can be life-threatening.

You could also try these ideas to try to ease the person’s distress:

About 60% of people with delirium recover within a week. Some people, however, take longer to recover, and some never return to exactly how they were before – this is more likely if the person is living with dementia. You should also consider whether the person may be in pain (especially chronic pain such as arthritis), which has worsened, and they are struggling to communicate.

Delirium cannot always be prevented, but there are things you can do to reduce the risk.

When someone has delirium, the symptoms come on very quickly, over the course of one or two days or even a few hours, whereas dementia develops gradually over months or years. The symptoms of delirium also tend to vary a lot throughout the day.

Sundowning is a state of intense confusion that occurs in many people with dementia, typically in the evening. A person who is experiencing sundowning will often be very anxious and confused, with a strong sense of being in the wrong place. Although the symptoms can be similar, sundowning is not a type of delirium. Read more about sundowning.

Most people with delirium start to improve within a few days, especially if the root cause is identified and addressed. Some people, however, take longer to recover and may have symptoms of delirium for weeks or months after initially becoming unwell. Some people never fully return to how they were before.

There is no specific cure for delirium. However, it can often be successfully treated if any underlying causes are addressed, for example by prescribing medication to treat an infection, and the person is well supported.

Delirium can indicate an infection which, if not treated, could lead to medical complications such as sepsis, which can become life-threatening.

Dementia usually develops slowly over time. However, in some types of dementia, symptoms can get worse quite suddenly. For example, a person with vascular dementia may have times when their symptoms stay the same and then worsen quickly. A stroke can also cause a sudden increase in dementia symptoms.

It is important not to assume that sudden changes in a person with dementia are simply the result of their condition progressing, and to seek advice from a medical professional to rule out delirium.

To speak to a specialist dementia Admiral Nurse about alcohol-related brain damage or any other aspect of dementia, please call our free Dementia Helpline on 0800 888 6678 (Monday-Friday 9am-9pm, Saturday and Sunday 9am-5pm, every day except 25th December or email helpline@dementiauk.org.

If you prefer, you can book a phone or video appointment with a specialist dementia Admiral Nurse in our virtual clinics.

Nat reflects on her experience of being a young carer and the support she received from the Nationwide dementia clinic.

Tim reflects on the stigma that is often attached to dementia and the importance of the Black, African and Caribbean Admiral Nurse clinics.

Katrina reflects on the support she has received from her Admiral Nurse, Rachel, since her husband was diagnosed with young onset dementia.

Sundowning is a term used for the changes in behaviour that occur in the evening, around dusk, and experience agitation or anxiety.

Read personal stories from people living with a diagnosis, their family members and friends - as well as our dementia specialist Admiral Nurses.

Whether you have a question that needs an immediate answer or need emotional support when life feels overwhelming, these are the ways our dementia specialist Admiral Nurses can support you.