The system failed to support my family with dementia

Julie writes about how her Admiral Nurse Rachel helped her understand the complexities of the health and social system – and her husband's diagnosis - when no one else could.

Parkinson’s and dementia are both progressive conditions that affect the brain, and for some people, both of them can develop together, creating a combination of symptoms that can be particularly challenging. On this page, our dementia specialist Admiral Nurses explain what Parkinson’s is, its symptoms, treatment options and what happens when someone develops both dementia and Parkinson’s.

Parkinson’s is a condition in which a part of the brain called the substantia nigra loses nerve cells. This loss of nerve cells results in a reduction of a substance called dopamine, which is important for the regulation of movement of the body. As dopamine levels decrease, the person’s movements become slower.

Most people with a diagnosis of Parkinson’s do not go on to develop dementia – although about a third will, usually in the later stages. This is known as ‘Parkinson’s with dementia’ and may also be referred to as Lewy body dementia.

Symptoms that can point to Parkinson’s may include, but are not limited to:

As mentioned, Parkinson’s is caused by a loss of nerve cells in the substantia nigra part of the brain. This is believed to be the result of a combination of genetic and environmental factors.

It is estimated that Parkinson’s affects about one in 500 people and it is currently thought that it may be due to a combination of genetic and environmental causes. About one-fifth of people diagnosed with Parkinson’s are under 40 years old, but it is more common in people over the age of 50.

Research into Parkinson’s has found a number of genetic factors that increase a person’s risk of developing the disease, although it is not clear why. In rare cases a faulty gene can be passed to a child by their parents which leads to Parkinson’s, but this is not common.

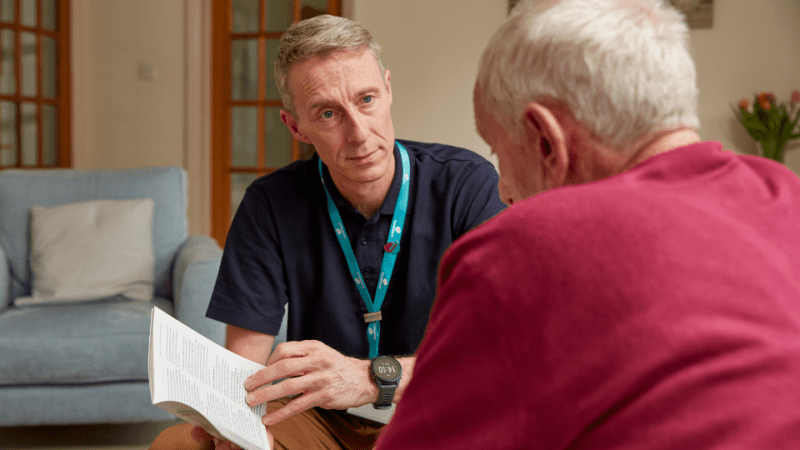

While there is no one test that can conclusively diagnose Parkinson’s, the GP should make an initial assessment of the combination of symptoms, take a medical history and carry out a physical examination.

If the GP does suspect Parkinson’s, the person should be referred to a specialist, such as a neurologist, who specialises in the brain or nervous system, or a geriatrician who specialises in conditions impacting older people.

During the appointment, the specialist will review the person’s movement through physical exercise and may also request specialised brain scans to rule out any other conditions that could be causing the symptoms.

People who have Parkinson’s are more likely to develop specific types of dementia, the symptoms of which develop over time. Initially, the symptoms may be quite mild, with progression being seen over time.

Around a third of people with Parkinson’s will develop dementia. This is because the disease that causes Parkinson’s is very similar to the one that causes dementia with Lewy bodies.

Yes, Parkinson’s dementia is a type of dementia that is categorised by an initial diagnosis of Parkinson’s, with symptoms of dementia developing at least a year post diagnosis.

If a person develops dementia symptoms before or alongside movement symptoms, specialists are likely to make a diagnosis of Lewy body dementia. However, if the symptoms of dementia develop a year after the onset of movement symptoms, the person is likely to be given a diagnosis of Parkinson’s dementia will be given. Find out more about Lewy body dementia.

When someone is living with Parkinson’s and dementia, symptoms can change from day to day or even hour to hour depending on the person. The symptoms can be very similar to Lewy body dementia, such as:

In addition to memory and thinking issues, someone with Parkinson’s dementia may experience;

If someone is having memory issues and already has a diagnosis of Parkinson’s, it is important for them to visit their GP, who will discuss any changes, their impact on the person’s life and how long they have had them. Find out more about getting a dementia diagnosis.

Currently, there is no cure for Parkinson’s, but research is ongoing.

With Parkinson’s the interventions are focused on support, management of the changes, and working with the person and their family to ensure they can live as well as possible with the condition. The physical effects of Parkinson’s can be managed by:

If the person with Parkinson’s has significant communication or cognitive issues, they can be managed by:

Bear in mind that a person’s understanding can often be well preserved even if they cannot communicate verbally.

It is a good idea for the person with Parkinson’s dementia and their family to have a needs assessment to look at what support the person with the diagnosis needs, a carer’s assessment to look at support for their family, and a financial assessment to see if they qualify for funding for any of this support. This will enable the family to receive the necessary advice and support to live as well as possible.

Staying active is important for people with Parkinson’s and dementia, helping to manage thinking and memory. It should be based on their interests and abilities.

While there is no specific diet that should be followed, a healthy and balanced diet is recommended for people with Parkinson’s dementia. It is important to consider the person’s needs, in particular if they have difficulties with swallowing. If you need advice on nutrition for a person with Parkinson’s dementia, contact their GP.

For more information visit parkinsons.org.uk or call 0808 800 0303. You can also phone our free Dementia Helpline to speak to a dementia specialist Admiral Nurse about Parkinson’s disease on 0800 888 6678 (Monday-Friday 9am-9pm, Saturday and Sunday 9am-5pm), email helpline@dementiauk.org or you can book an appointment by phone or video call.

Julie writes about how her Admiral Nurse Rachel helped her understand the complexities of the health and social system – and her husband's diagnosis - when no one else could.

Understand what Lewy body dementia is, what the symptoms are and what treatment is available.

Phil highlights the difference it makes when someone living with dementia receives appropriate support in the workplace. He urges employers not to "write someone off" because of their diagnosis.

While both Alzheimer’s disease and Parkinson’s dementia are types of dementia, they are different conditions. Often, people with Alzheimer’s disease will show difficulties with language earlier and are unable to form new memories, which is not the case with Parkinson’s.

Most people with a diagnosis of Parkinson’s do not go on to develop dementia – although about a third will, usually in the later stages.