Grief, bereavement and loss

The death of someone close is often a shock and it is hard to prepare yourself for how you may feel following a loss.

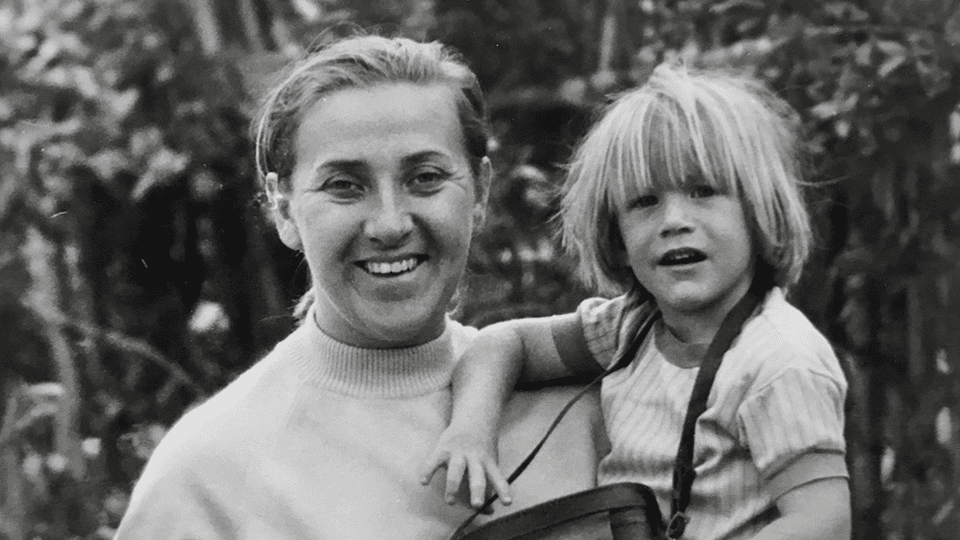

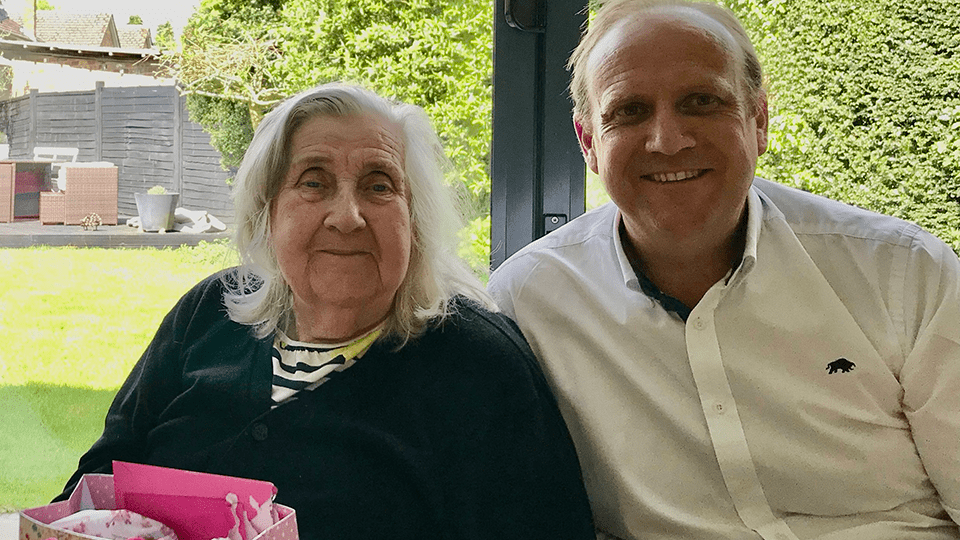

Steve reflects on the grief journey since his mum, who lived with Alzheimer’s disease, died in 2022.

As a society, I don’t think we’re good at talking about grief and loss. I know I’ve found it difficult personally. It’s been three years since Mum died, but my journey of grieving her goes on. And while I know nobody’s journey is the same, I know how lonely it can feel when you’re trying to process the loss of someone you love.

It may sound strange, but my grieving didn’t begin when Mum died. Rather, it was a gradual process unfolding with each passing month after her diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease at the age of 77. For years, I had been losing pieces of her and struggling to process each loss. The beautiful, and often formidable woman I’d always looked up to was becoming unrecognisable.

This process of loss was devastating for our family, and in particular my dad, who was her primary carer. He saw it as his duty to take care of Mum, and there was a real reluctance to ask for help until things got extremely difficult.

And so, long before we grieved Mum’s actual death, we mourned the many small losses that occurred throughout her illness – the loss of shared memories, of recognition, of the relationship as it once was.

It sounds strange to say there was a sense of relief when Mum died. But with dementia, as with grief, nothing is straightforward.

While Dad wouldn’t have had it any other way, his caring role had meant he was completely exhausted, emotionally and physically. He’d been in a non-stop cycle of round-the-clock care, neglecting his own sleep and wellbeing. It wasn’t sustainable. For so long, I too had been in a state of constant worry. Dementia had taken over our lives, dictating so many elements of it in such a cruel way.

So when Mum died, our first feeling was relief.

But then, with time, a new emotion arose – a deep anger with the world and everything in it. A relentless anger that wouldn’t abate even after considerable time had elapsed. I’d ruminate on questions like, ‘Why did this have to happen to us?” Mum deserved better. And with nobody to target the anger at directly, I sometimes fell into the trap of targeting it at everyone.

For carers who have devoted years to looking after their loved one, the sudden absence of purpose can be as devastating as the loss itself. The identity of ‘carer’ becomes so deeply ingrained that its absence leaves a profound void. Who are you when you’re no longer needed in that all-consuming role?

I also found that when in the midst of this caring role, relationships can fall by the wayside. There are only so many hours in a day, week and month. Time that you would have spent with family and friends is spent keeping your loved one safe, especially in the later stages of dementia. When they die, it’s very hard to just pick up old relationships and friendships as if nothing has happened. Reconnecting can be very challenging. Things change and people move on.

This disconnection and isolation can give time and space for negative thoughts to creep in. This is why I think it’s so important to be open about your grieving journey. It shouldn’t be a path walked alone.

After Mum died, I saw firsthand how different people handle loss. While some closed off and didn’t want to talk about the anguish of the dementia journey, others were keen to focus on the positive. To celebrate the life of an incredible woman. To start conversations on dementia, to fundraise and to ensure others in the same situation know they aren’t alone.

This is the path I have chosen. Rather than reflecting on or marking Mum’s death, I want to remember the positive life she had and use it as my inspiration. This approach has given me a sense of purpose and direction, allowing me to honour Mum’s memory while making a tangible difference. I am a long-time supporter of Dementia UK – and have dedicated myself to helping the Charity increase the number of dementia specialist nurses, known as Admiral Nurses. We are closing in on the 500 mark, which makes me incredibly proud.

Supporting the Charity helps to channel a sense of loss into something constructive, fostering a sense of hope and connection with others who have experienced similar grief.

I feel it’s what Mum would want too.

Reaching out for help can present a real barrier – especially for men. It involves being open and honest about how we feel and how we behave. That level of vulnerability is extremely challenging for many, particularly after years of focusing solely on another person’s needs while suppressing your own.

Support groups, specifically for those who have lost someone to dementia can be invaluable, as they understand the distinctive nature of this grief. These spaces acknowledge both the relief and the guilt that can accompany the end of a dementia journey, without judgment.

I have had firsthand experience calling the Dementia UK Helpline and would wholeheartedly recommend phoning and speaking to a dementia specialist Admiral Nurse. I remember calling initially and being put in touch with Admiral Nurse Joe. That was the first of many calls. He was so understanding and there was a level of male-to-male empathy which I found very reassuring. I remember crying down the phone and I don’t cry often.

Dementia UK’s grief, bereavement and loss webpage also has useful information and contacts.

I think that healing begins when we allow ourselves permission to both mourn and move forward, recognising that continuing to live fully doesn’t diminish the love we felt, nor the importance of the care we provided. It’s possible, with time and support, to honour that relationship while reclaiming parts of ourselves that were necessarily set aside during the caregiving years.

The road is neither straight nor easy, but each small step – whether it’s reconnecting with an old friend, pursuing a neglected interest or simply acknowledging difficult feelings – represents progress on the journey toward healing.

The death of someone close is often a shock and it is hard to prepare yourself for how you may feel following a loss.

Caroline Scates, our Admiral Nurse Professional & Practice Development Facilitator, talks on communicating about the difficult topic of death and dying.

Hear from people who have experienced feelings of guilt throughout their dementia journey and read advice from our Chief Admiral Nurse on how to help manage these feelings.