Tim’s story – “There is stigma around dementia”

Tim reflects on the stigma that is often attached to dementia and the importance of the Black, African and Caribbean Admiral Nurse clinics.

Tim reflects on the stigma that is often attached to dementia and the importance of the Black, African and Caribbean Admiral Nurse clinics.

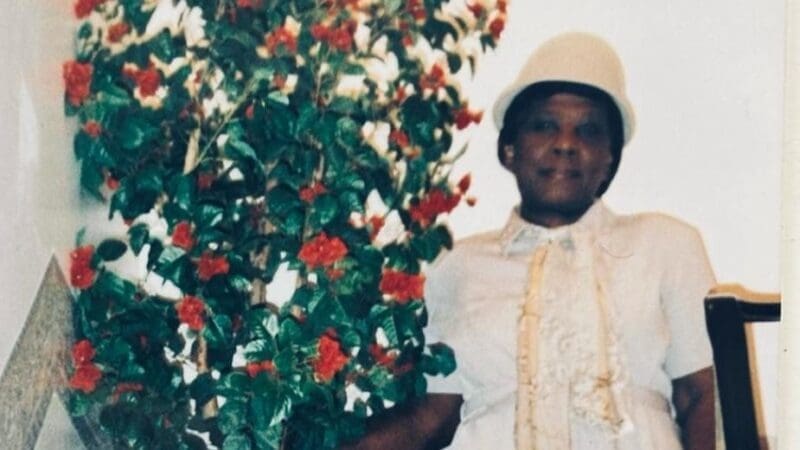

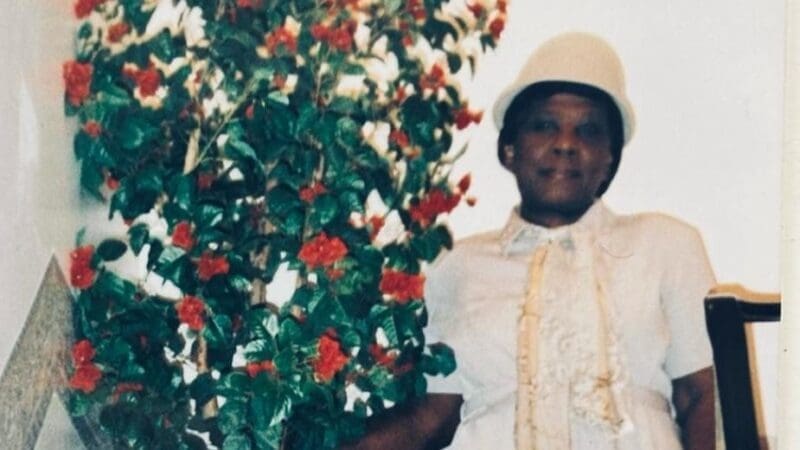

My grandma, Valera, was a truly amazing woman. She was generous, reserved, and had a dry and warm sense of humour – she was typical of her generation.

My grandma was born on the Caribbean island of Barbuda in 1936. In the early 1950s, my grandparents answered the call to come to the UK as part of the Windrush generation, hopeful about helping to rebuild the mother country after the war. They arrived in the UK during autumn, and the reality was very different from what they had imagined. The cold, grey weather came as a shock, but my grandma wasn’t one to complain; she was pragmatic to her core.

My grandparents settled in Leicester and shifted between whatever jobs they could find, including hotel and factory work. My grandma became well-known at her local church, where there was a large Barbudan community. Her resilience and determination have become part of who I am today.

My mum, her eldest daughter and who was only 11 at the time, was still living in Barbuda with my great-grandparents. I can’t imagine how painful it must have been for my grandma to have a fractured family. When my grandparents finally established themselves, my mum joined them in Leicester. She flew across alone, completely unaware of what she was coming to.

Sadly my mum passed away when I was 12. My uncle also died in a car accident the same year, so my grandma lost two of her children within six months. At a point in her life when she should have been resting, my grandma stepped up and took on guardianship of me and my younger brother. She never had a break in her life. She laid out a clear path for me and insisted that I go to college and then onto university. I always knew where I stood and felt safe. She kept me on an incredible trajectory that got me to where I am today.

As an adult, I moved to Liverpool and had my own family. I visited my grandma when I could and, when I did, I started to notice some small changes in her behaviour. She’d call me by my older brother’s name but then recognise me within a few minutes. She would ask about my mum, even though she’d passed away such a long time ago. I noticed the concerned looks between aunties and uncles.

For years, my grandma’s condition seemed stable, apart from the odd memory lapse. Then, in the last two years, everything seemed to nosedive. Her mental and physical health started to decline, and we could see she needed help.

That’s when things became really difficult. We kept taking my grandma to the GP, but it felt like a constant cycle of being told, “She’s old; here are some antibiotics; here’s some pain relief.” We didn’t know where to turn. It took months to get my grandma referred for a memory test, which resulted in her being diagnosed with vascular dementia.

There’s a stigma attached to dementia in society, and the Caribbean community is no exception. Dementia can be seen as a mental health condition rather than a physical one. My grandma was experiencing a physical illness that was affecting her brain. She stopped going to the church she’d attended for 50 years because people would ask her questions that she couldn’t answer, and it became difficult for her to be in those environments.

My family was determined to keep my grandma at home and look after her themselves. It’s almost a matter of pride in our community, and we don’t ask for help until it’s too late. But looking back, I wonder if we could have done more to advocate for the support my grandmother needed after her diagnosis. I feel sad that my children didn’t get to spend more time with her and I wonder if that might have been possible if she’d had more support in place.

My grandma ended up being admitted to hospital when she was in the later stages of dementia. She was unable to care for herself, was malnourished, and the doctors were concerned that she might have sepsis. The hospital building was worn down and grimy. It was heartbreaking to see her in that environment. I just kept thinking, “I don’t want my grandma to be here.” But the nurses were incredibly kind and that made a huge difference.

My grandma was a fighter right to the end. When the hospital health professionals thought she was close to the end of her life, she just kept going. That was so like her. She spent her final weeks in a care home, which was a much more comfortable environment than the hospital.

My grandma passed away in January this year, and it still feels raw. But I also feel relieved that she is finally at peace.

I’ve thrown myself into honouring my grandma’s memory. I recently completed the Mount Toubkal trek in Morocco alongside a team of colleagues as part of our charity partnership with Dementia UK. I’ve found fundraising and raising awareness of her experience has been a powerful healing tool. I climbed 4,167m and raised £2,700 for Dementia UK. The team raised £60,000 in total: an amazing achievement.

Every step I took up that mountain was a tribute to my grandma and everything her generation sacrificed. When it got really hard, what kept me going was this notion that throughout her life she had these incredible mountains to climb and overcame them one after the other – no matter what was thrown in her way. Even throughout her struggles with dementia, I could see her determination to keep going, and she never stopped smiling.

Black and African-Caribbean people in the UK are 20% more likely to develop dementia. When you put that alongside the Windrush scandal, it feels like my grandma’s generation has faced barriers at every single stage of their lives. By raising funds and awareness, I’m not just seeking justice for one incident. It’s about recognising the sacrifices my grandma made and ensuring something better comes from it for future generations.

Nothing I do will compare with what my grandma’s generation have had to endure in their lifetime, but I can make sure their story is told, and I can advocate for better, more equitable care going forward. I know my grandma would be proud.

When I found out about the new dementia specialist Admiral Nurse clinics service for the Black, African and Caribbean communities, it really touched me. The service provides culturally tailored dementia support for people from these communities, so they can get the help they need and deserve. Although my grandmother died before we could access the service, it gives me hope that the need for a specialist service has been recognised and put into action.

If I could give any advice to families in similar situations, it would be to reach out for support as early as possible. Our culture tells us that we can deal with everything ourselves; it’s part of our story and how the generation before us survived. But there is specialist support available for you and your family. You are not alone on this journey.

Tim reflects on the stigma that is often attached to dementia and the importance of the Black, African and Caribbean Admiral Nurse clinics.

Katrina reflects on the support she has received from her Admiral Nurse, Rachel, since her husband was diagnosed with young onset dementia.

Linda attended a Nationwide clinic and reflects on the advice she received from Admiral Nurse, Emma.