Susan’s story: "Stigma around dementia means that many find it hard to accept they are affected by the condition"

Volunteer Ambassador Susan Ogden cared for her husband Peter, who had Alzheimer’s disease, until he sadly died on New Year’s Day 2021.

Susan and Peter, September 2007

Peter was a larger than life character. He worked as a teacher of challenging children, and was well liked by all his colleagues. We loved to travel, and after we took early retirement, we had wonderful holidays in America, across Europe, and in Israel, where our daughter was working.

Peter was definitely ‘a man with a shed’ and in his garden workshop he could turn his hand to anything practical, even if he was terribly bad-tempered if anything went wrong!

In 2011, Peter had an operation to remove a benign tumour on his parotid gland, which led to some memory problems. Looking back, though, things hadn’t been quite right for some time. I remember one incident where we made a familiar journey, and Peter – who had an instinctive sense of direction – took a wrong turn. He became extremely angry when I pointed it out.

Peter was initially diagnosed with mild cognitive impairment, and then, in 2014, with Alzheimer’s disease. But he was a very private person and found it difficult to talk about his dementia.

At the time, I was reading a lot about people’s experiences with dementia, including the journalist and presenter John Suchet’s book about his wife, Bonnie. It was there that I first heard of Admiral Nurses.

I noticed that they were launching a service in our borough and went along to an information day with Peter. Dementia UK’s Chief Admiral Nurse and CEO, Hilda Hayo, gave a talk, and I found her inspirational. After her talk, she spoke to us – she was able to really engage with Peter.

I was also introduced to Rachel, a dementia specialist Admiral Nurse. She first came to see us in May 2016. She was with us for two hours, and the compassion, kindness and time she gave us was wonderful. From that point on, Rachel visited us regularly.

“Our Admiral Nurse knew all the right things to say”

Things got really difficult that summer. We went on holiday with our daughter, and after being with her dad for a week, under the same roof, she could see the deterioration. She told me we couldn’t go on living like that.

When we got back, Rachel arranged for us to talk to a social worker to fix up some respite. Peter was angry but Rachel knew all the right things to say, and with her persuasion, he grudgingly accepted.

On the day, Rachel had to come and physically take Peter to the dementia facility. I heard her helping him putting his shoes on, saying, “Can I help you, flower?” He angrily retorted, “I’m not your flower!” She asked him what he would like her to call him, and he said, “Sir” – and from then on, she did.

Peter seemed to enjoy his week in respite, although it was clear he didn’t have a clue what was going on. But when he spent a second week there, he attacked two of the carers. The psychiatrist who was sent to assess him said, “Susan, I’m struggling – he’s presenting so well.” That was what he was capable of doing.

From that point, Peter never returned home. He was sent first to an old people’s home with a dementia unit, which just wasn’t suitable for him. He walked the floors, didn’t change his clothes – he totally changed in that time because he was so disorientated.

He was sectioned after again attacking two staff members and was sent to a psychiatric hospital, and then to a unit for men with challenging behaviours. My grandchildren used to get upset about their grandad – they were frightened to visit him because there were lots of men behaving strangely.

If Peter had understood what was going on, he wouldn’t have tolerated a day of it, yet alone four years. He would have burst his way out.

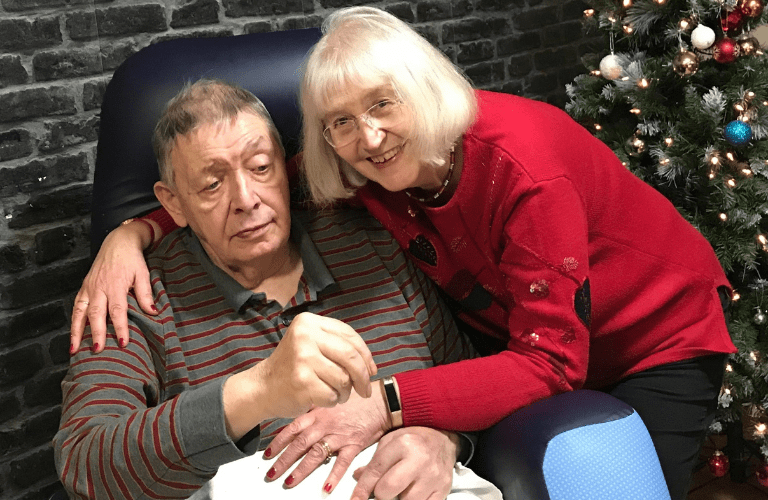

Susan and Peter, Christmas 2019

“Peter was never run of the mill”

Because of the pandemic, I wasn’t able to visit Peter throughout lockdown. I was angry, and threw myself into campaigning on care home visiting and how the situation had been handled by the Government.

Sadly, Peter died on New Year’s Day 2021. I didn’t see him until the day he died and was so shocked by his appearance that I just froze. He was in agony, in semi-darkness with the curtains closed, with no one with him. That image will stay with me forever.

Peter was never run of the mill. His carers said how funny he was – he had a caustic wit, and although his speech was often nonsensical, when friends came to visit, he was animated. They must have triggered deep memories in him – just by touching them, he could relate to them.

There are some people who are capable of living well with dementia, but Peter hated every minute of it. Rachel was a lifeline for us both – she knew how to relate to Peter, and I’m still in touch with her. The compassion, kindness and time she gave us went far beyond anything we received elsewhere. Despite this, we have many happy memories and our lives will never be defined by dementia. In volunteering, I hope that I can make a difference to the lives of others.