Arthur’s story

Arthur explains how to get the best out of going on holiday with a person who has dementia.

Frontotemporal dementia (FTD) is an umbrella term for a group of dementias that mainly affect the frontal and temporal lobes of the brain, which are responsible for personality, behaviour, language and speech.

Unlike other types of dementia, memory loss and concentration problems are less common in the early stages.

FTD is a rare form of dementia affecting around one in 20 people with a dementia diagnosis.

In FTD, there is an abnormal build-up of proteins within the brain, which damages the cells.

It is not known why this occurs, but it is thought to have a genetic link in about one third of people with the diagnosis.

FTD is most common in people aged 40 to 60 but can also affect younger or older people.

There are two types of FTD – behavioural variant FTD (bvFTD) and primary progressive aphasia (PPA).

There are three types of PPA, which all tend to affect language rather than behaviour.

Semantic variant or semantic dementia (SD)

Nonfluent variant or progressive nonfluent aphasia (PNFA)

Logopenic variant or logopenic aphasia (LPA)

Progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) is a frontotemporal dementia. It is characterised by difficulties with balance, movement, vision, speech and swallowing. It is caused by progressive damage to the cells in the brain that control eye movements.

It affects around 4,000 people in the UK. Some also experience changes in their behaviour, clumsiness or stiffness and cramped handwriting. Because its initial symptoms can resemble other conditions such as Alzheimer’s or Parkinson’s, it can be difficult to diagnose.

For further information and support, visit the PSP Association website.

Corticobasal degeneration (CBD) is a frontotemporal dementia. It is a rare condition where brain cells become damaged over time and certain sections of the brain start to shrink. It is a progressive condition. This means that the initial symptoms will become more severe over time, and new symptoms may also develop.

Initial symptoms of CBD include

As the condition progresses, symptoms become more wide ranging and troublesome, such as

Find more information and support at the PSP Association website.

Getting a diagnosis of FTD can be difficult for reasons including:

However, if you are concerned that someone may have FTD, it is important to encourage them to see their GP.

If they are reluctant, you could contact the GP by phone, email or letter and outline your concerns – while the GP will not be able to breach the person’s confidentiality, they should consider the information and decide whether to call them in for an appointment or arrange a home visit.

If possible, go to the appointment with the person so you can share your views and concerns.

The GP should:

If the person needs further investigations, they should be referred to a specialist in FTD for a comprehensive assessment of attention, memory, fluency, language, visuospatial abilities and behaviour changes.

They may also have an MRI scan of the brain.

To speak to a dementia specialist Admiral Nurse about FTD or any other aspect of dementia, please call our free Dementia Helpline on 0800 888 6678 (Monday-Friday 9am-9pm, Saturday and Sunday 9am-5pm, every day except 25th December), email helpline@dementiauk.org or you can also book a phone or video appointment with an Admiral Nurse.

Our virtual clinics give you the chance to discuss any questions or concerns with a dementia specialist Admiral Nurse by phone or video call, at a time that suits you.

Arthur explains how to get the best out of going on holiday with a person who has dementia.

John’s wife Linda was diagnosed with young onset Alzheimer’s disease at the age of 53. They have been supported by Admiral Nurse Lesley.

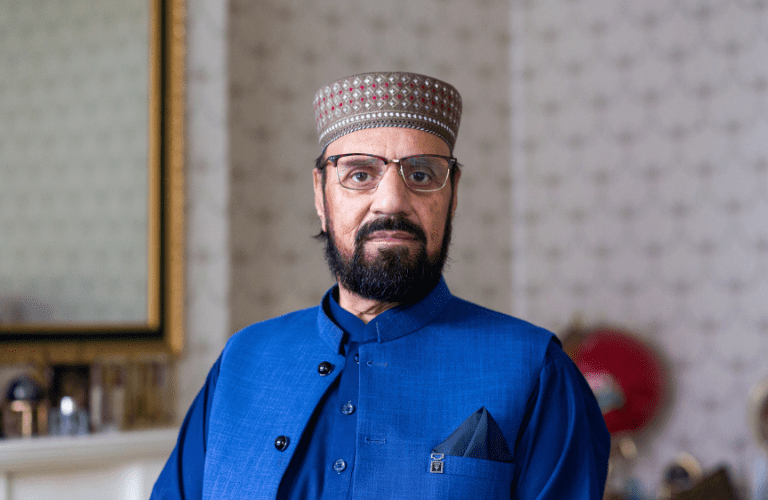

Maq was diagnosed with frontotemporal dementia in 2010 at the age of 54. Here he reflects on how the condition affects his day-to-day life.